Weekly Anti-racism NewsletteR

Because it ain’t a trend, honey.

-

Taylor started her newsletter in 2020 and has been the sole author of almost one hundred blog mosts and almost two hundred weekly emails. A lifelong lover of learning, Taylor began researching topics of interest around anti-racism education and in a personal effort to learn more about all marginalized groups. When friends asked her to share her learnings, she started sending brief email synopsises with links to her favorite resources or summarizing her thoughts on social media. As the demand grew, she made a formal platform to gather all of her thoughts and share them with her community. After accumulating thousands of subscribers and writing across almost one hundred topics, Taylor pivoted from weekly newsletters to starting a podcast entitled On the Outside. Follow along with the podcast to learn more.

-

This newsletter covers topics from prison reform to colorism to supporting the LGBTQ+ community. Originally, this was solely a newsletter focused on anti-racism education, but soon, Taylor felt profoundly obligated to learn and share about all marginalized communities. Taylor seeks guidance from those personally affected by many of the topics she writes about, while always acknowledging the ways in which her own privilege shows up.

Ahmaud Arbery

This week, I’m covering the Ahmaud Arbery case and the trials of his murderers, Gregory McMichael, his son Travis McMichael and William "Roddie" Bryan Jr. Right. Currently, we are at day 5 of the trial so I will continue to share more in my weekly newsletters as the case develops. At first, the killing of Ahmaud Arbery in February 2020 went largely unnoticed. It wasn't until a video of the shooting surfaced on May 5, 2020, that the Black man's death drew nationwide attention.

Hi Friends!

Welcome to Issue 41 of this newsletter! This week I’m covering the Ahmaud Arbery case and the trials of his murderers, Gregory McMichael, his son Travis McMichael and William "Roddie" Bryan Jr. Right. Currently, we are at day 5 of the trial so I will continue to share more in my weekly newsletters as the case develops. At first, the killing of Ahmaud Arbery in February 2020 went largely unnoticed outside the South Georgia community where the 25-year-old lived and died. It wasn't until a video of the shooting surfaced on May 5, 2020, that the Black man's death drew nationwide attention. Three white men have all pleaded not guilty to Arbery’s murder. I was shocked while researching this case that four prosecutors have already been appointed to this case and recused themselves because they either are connected to or agree with the murderers. I was shocked that Judge Timothy Walmsley said the court "found that there appears to be intentional discrimination" on the part of the defense after they chose only one single Black juror and twelve white ones—yet still has allowed the case to go forward. How can Black Americans ever have justice when white supremacy continues to infiltrate and dominate our systems of supposed law and order? Let’s get into it.

Let’s Get Into It

The Timeline

February 23, 2020: Ahmaud Arbery is fatally shot

Ahmaud was out for a jog in mostly white Satilla Shores neighborhood near Brunswick.

Gregory McMichael and his son Travis McMichael pursed Arbery in a truck, both armed with guns.

Gregory McMichael is former police officer and investigator in the local District Attorney's Office.

Gregory McMichael told police he and his son had pursued Arbery because they suspected he was responsible for a string of recent purported burglaries in the neighborhood. There had only been one burglary, reported more than seven weeks prior to the shooting.

A third man, William "Roddie" Bryan, also joined the pursuit and recorded the shooting on his cellphone.

During the struggle, Arbery is shot three times, twice in the chest, after which he slumps to the ground.

It took 74 days after Arbery’s death for the men to be arrested and charged.

February 27, 2020: AG's office learns Brunswick Judicial Circuit district attorney recusing herself

Brunswick Judicial Circuit District Attorney Jackie Johnson recused herself from the case, citing Gregory McMichael's position as a former investigator in her office.

April 7, 2020: Second prosecutor recuses himself, lays out a defense of the McMichaels

The case was then taken over by District Attorney of the Waycross Judicial Circuit, George Barnhill.

Barnhill’s son worked in Johnson's office and had previously worked with Gregory McMichael on a previous prosecution of Arbery.

He only asked to relinquish the case in early April at the request of Arbery's mother, though he knew about the personal conflict sooner.

Barnhill said he believed the McMichaels' actions were "perfectly legal."

Finally, Atlantic Judicial Circuit District Attorney Tom Durden is appointed to the case.

May 5, 2020: Video of the shooting surfaces

May 7, 2020: The McMichaels are arrested

May 11, 2020: A fourth prosecutor takes over

AG Carr announced a fourth prosecutor, Cobb County District Attorney Joyette Holmes, would lead the case after Durden had asked to step down due to a lack of sufficient resources.

May 21, 2020: Bryan is arrested

June 4, 2020: Travis McMichael used racial slur after shooting Arbery, GBI agent testifies

Bryan tells investigators he heard Travis McMichael use the n-word after shooting Arbery dead.

GBI Assistant Special Agent in Charge Richard Dial said there were "numerous times" Travis McMichael used racial slurs on social media and in messaging services.

Bryan also had several messages on his phone that included "racial" terms, Dial said.

June 24, 2020: All three suspects indicted on murder charges

Glynn County Grand Jury indicted Gregory and Travis McMichael and Roddie Bryan on malice and felony murder charges.

McMichaels face several other charges, including aggravated assault, false imprisonment and criminal attempt to commit false imprisonment.

Bryan also faces a charge of criminal attempt to commit false imprisonment.

July 17, 2020: Suspects plead not guilty

November 13, 2020: Bond denied for the McMichaels

April 28, 2021: Suspects are indicted on federal hate crime charges

Federal prosecutors announced a grand jury had indicted the McMichaels and Bryan on hate crime and kidnapping charges.

Each were charged with one count of interference with rights and one count of attempted kidnapping.

Gregory and Travis McMichael were also charged with using a firearm in relation to a crime of violence.

May 11, 2021: Suspects plead not guilty in federal court

October 18, 2021: Jury selection begins

November 3, 2021: A jury is seated

It took 2 1/2 weeks for the jury selection process to be completed.

A panel of 12 people -- 11 white jurors and one Black juror -- was seated on Wednesday, November 3.

Prosecutors for the state accused defense attorneys of disproportionately striking qualified Black jurors and basing some of their strikes on race.

Judge Timothy Walmsley said the court "found that there appears to be intentional discrimination" on the part of the defense — yet still has allowed the case to go forward.

What’s a Citizen’s Arrest?

Defense attorneys will likely argue that the men’s actions were protected by Georgia’s citizen’s arrest law, which at the time allowed a person to detain someone whom they believe just committed a crime.

The attorneys may claim the men acted in self-defense while attempting to carry out a legitimate citizen’s arrest of Arbery, whom they suspected of burglary.

Georgia’s outdated and dangerous citizen’s arrest law — one that was created in an era of slavery and emboldened citizens to act on their worst biases — has since been repealed.

Georgia’s citizen’s arrest statute had its origins in the Civil War era. Passed in 1863, when slavery was still considered legal by Southerners despite the Emancipation Proclamation, the law stated that a private person could “arrest an offender if the offense is committed in his presence or within his immediate knowledge.”

Also factoring into the Arbery trial are Georgia’s open carry law (which makes it legal to openly carry firearms in the state with the proper permits) and “stand your ground” law (which allows for the use of deadly force if a person reasonably believes it is necessary to prevent death or severe bodily injury).

I am absolutely heartbroken for Ahmaud Arbery and his family. His parents who had to sit in a courtroom with their son’s murders and watch footage of their child’s death—lynched in the street, called a nigger by an ex-police officer in broad daylight in America. As always, I am devastated, disappointed, exhausted, but never defeated, in my fight for racial justice.

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

The Black Panther Party

The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense was founded in October 1966 in Oakland, California by Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale and the first point of their Ten Point Platform and Program was “We want freedom.” In 1968, the FBI’s first director, J. Edgar Hoover called the Black Panthers, “One of the greatest threats to the nation’s internal security,” because they were angry, organized and defiant. COINTELPRO wanted the Black Panthers exterminated, disgraced and omitted from the history books — and largely succeeded. Today, we focus on the truth of their legacy.

“Black people need some peace. White people need some peace. And we are going to have to fight. We’re going to have to struggle. We’re going to have to struggle relentlessly to bring about some peace, because the people that we’re asking for peace, they are a bunch of megalomaniac warmongers, and they don’t even understand what peace means.”

Hi Friends!

Welcome to Issue 36 of this newsletter! This week’s topic is The Black Panther Party. Writing this newsletter was a clear reminder of why I began writing in the first place, because knowing our history matters, especially when the truth is constantly denied to us through the American public education system. The brief, yet impactful legacy of the BPP is both inspiring and devastating. The assassination of Chairman Fred Hampton has brought me to tears on more than one occasion. The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense was founded in October 1966 in Oakland, California by Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale and the first point of their Ten Point Platform and Program was “We want freedom.” In 1968, the FBI’s first director, J. Edgar Hoover called the Black Panthers, “One of the greatest threats to the nation’s internal security,” because they were angry, organized and defiant. COINTELPRO wanted the Black Panthers exterminated, disgraced and omitted from the history books — and largely succeeded. Today, we focus on the truth of their legacy. Let’s get into it.

Let’s Get Into It

Who Were The Black Panthers?

Founded in 1966 in Oakland, California, the Black Panther Party for Self Defense (BPP) was the era’s most influential militant Black power organization.

Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton founded the Black Panther Party for Self Defense with a slogan of “Power to the People.”

They were inspired by Malcom X and drew on Marxist ideology. The Civil Rights Movement seemed aimed at the Jim Crow South to Seale and Newton, and they wanted to create a movement in the North and the West.

While the Black Panthers were often portrayed as a gang, their leadership saw the organization as a political party whose goal was getting more African Americans elected to political office.

They wore leather jackets, black berets and walked in lock step formations.

They were a sophisticated political organization comprised of predominantly uneducated, young, poor, disenfranchised Black people who realized that through organization and discipline, they could use their talents and resources to make a real impact in their community.

They had a radical political agenda compared to non-violence advocates like Martin Luther King Jr (least we forget King was hated, a target of the FBI, assassinated and murdered).

While the Civil Rights Movement sought equality, the Black Power Movement assumed equality of person, and sought the opportunity to express that equality through pride.

Women made up about half of the Panther membership and often held leadership roles.

At its peak in 1968, the Black Panther Party had roughly 2,000 members.

The party enrolled the most members and had the most influence in the Oakland-San Francisco Bay Area, New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Seattle, and Philadelphia.

They worked with many non-Black folks and organizations, with Bobby Seale stating: “The biggest misconception is the FBI said that the Black Panthers hated all white folks. How could we hate white folks when we protested along with thousands of our white left radical and white liberal friends? We worked in coalition with each other, in coalition with the Asian community organizations and coalition with Native American community organizations, in coalition with Hispanic, Puerto Ricans and brown [people]. I had coalitions with 39 different organizational groups crossing all racial and organizational lines.”

The Ten Point Platform

We want freedom. We want power to determine the destiny of our Black Community.

We want full employment for our people.

We want an end to the robbery by the Capitalists of our Black Community.

We want decent housing, fit for shelter of human beings.

We want education for our people that exposes the true nature of this decadent American society. We want education that teaches us our true history and our role in the present day society.

We want all Black men to be exempt from military service.

We want an immediate end to POLICE BRUTALITY and MURDER of Black people.

We want freedom for all Black men held in federal, state, county and city prisons and jails.

We want all Black people when brought to trial to be tried in court by a jury of their peer group or people from their Black Communities, as defined by the Constitution of the United States.

We want land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice and peace.

Why Were They Feared By White America?

The New York Times wrote an article claiming responsibility for their portrayal of The Black Panther Party, stating: “The media, like most of white America, was deeply frightened by their aggressive and assertive style of protest,” Professor Rhodes said. “And they were offended by it.”

The media called them “antiwhite” (though the Panthers frequently called on ALL Americans to fight for equality) and constantly focused on their guns and militant style.

When discussing clashes with police, the media focused on the altercation, not the critique of police brutality — something Black America continues to deal with to this day. What went largely unreported was the fact that these conflicts stemmed not just from the Panthers, but also from the federal government.

It was not until years later that the Senate’s Church Committee would show how pervasively the F.B.I. worked against the Panthers and how much it influenced press coverage. It encouraged urban police forces to confront Black Panthers; planted informants and agents provocateurs; and intimidated local community members who were sympathetic to the group. The Panther-police conflict that inevitably followed played directly into the narrative that had been established: that the party was a provocative, dangerous organization.

What Did The Black Panthers Do?

Although created as a response to police brutality, the Black Panther Party quickly expanded to advocate for other social reforms:

Local chapters of the Panthers, often led by women, focused attention on community “survival programs.”

A free breakfast program for 20,000 children each day as well as a free food program for families and the elderly.

They sponsored schools, legal aid offices, clothing distribution, local transportation, and health clinics and sickle-cell testing centers.

They created Freedom Schools in nine cities including the noteworthy Oakland Community School.

They practiced copwatching, observing and documenting police activity in Black communities. They often did this with loaded firearms because they advocated for armed self defense. The BPP rejected nonviolence as both a tactic and a philosophy, emphasizing instead the importance of physical survival to the continuing struggle for civil and human rights.

Prominent Members

How Were They Destroyed?

The Mulford Act of 1967 in California was a state-level initiative that prohibited the open carry of loaded firearms in public spaces as a direct response to the BPP. The Black Panther Party sparked fear among policymakers, who translated these anxieties into legislation designed to undermine this social activism. Because the BPP relied on strategies (like having firearms) that were not widely used by mainstream civil rights activists, the group faced new forms of legal repression. Policymakers successfully employed gun control legislation to undercut the BPP. By criminalizing the BPP’s use of weapons on California streets, the Mulford Act weakened the BPP and provided opportunities to show them breaking the law.

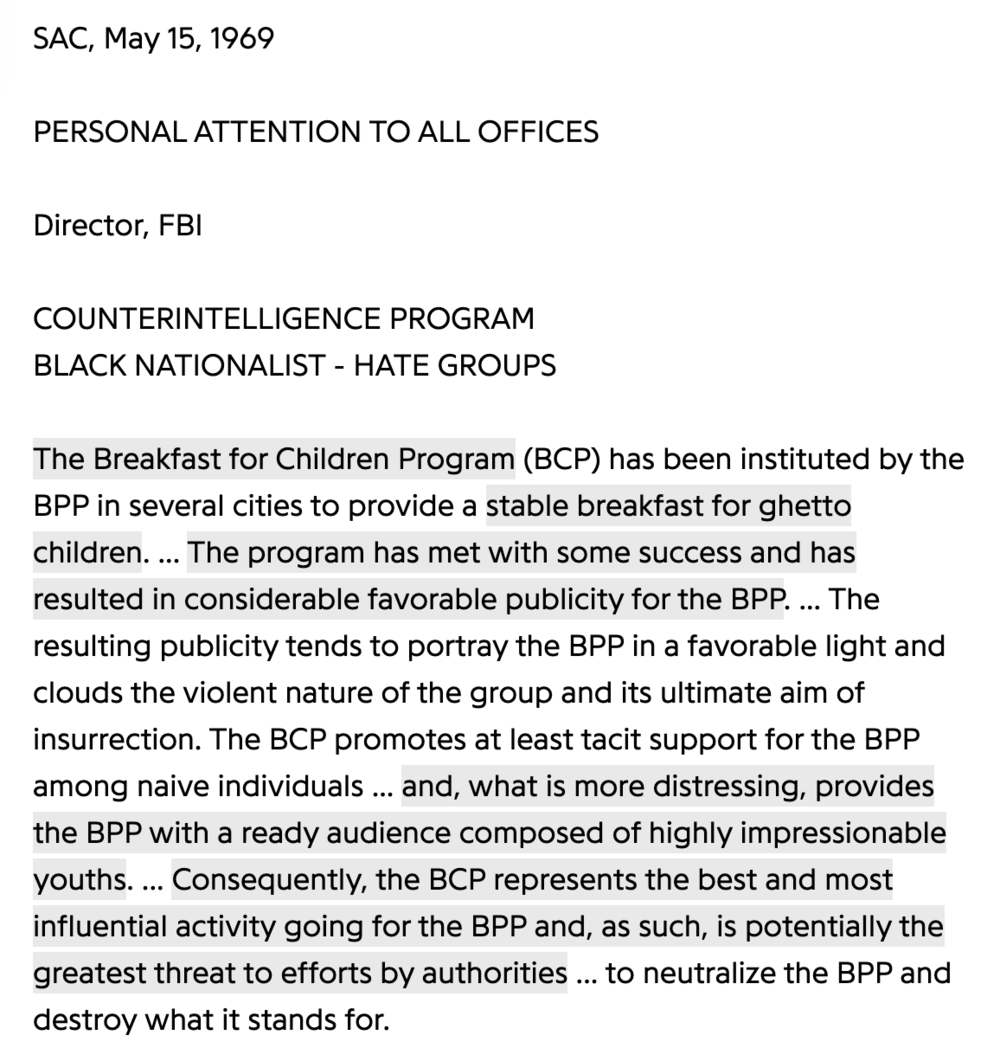

In 1969, COINTELPRO (a branch of the FBI aimed at surveilling, infiltrating, discrediting, and disrupting domestic American political organizations) targeted the Panthers for elimination — shown in various documents.

FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, who deemed the Black Panther Party a threat to American security, launched a counterintelligence attack against the group, which included infiltrators and deadly raids. By the time the group was dismantled in the mid-1970s, 28 members were dead. 750 Panthers were imprisoned. Systematically, the local and federal authorities dismantled the organization.

Read FBI director J. Edgar Hoover’s statement from May 15, 1969 calling “to neutralize the BPP and destroy what it stands for.’

Today, American children learn a false and warped history of The Black Panther Party. Teachers’ Curriculum Institute’s textbook History Alive! The United States Through Modern Times states: “Black Power groups formed that embraced militant strategies and the use of violence. Organizations such as the Black Panthers rejected all things white and talked of building a separate black nation.” Holt McDougal’s textbook The Americans reads: “Huey Newton and Bobby Seale founded a political party known as the Black Panthers to fight police brutality in the ghetto.” This same textbook then says, “Public support for the Civil Rights Movement declined because some whites were frightened by the urban riots and the Black Panthers.”

While there is so much more to unpack about The Black Panther Party and the legacies of some of its most prominent members, I hope this newsletter clarified a lot of omitted history. In a time when critical race theory is under attack, it becomes crystal clear how much has been warped by the media — from news channels to text books — and how much more we need the truth.

See ya next week!

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

Juneteenth

Juneteenth became national holiday this week. Juneteenth is an incredibly meaningful moment because enslaved people longed for freedom for generations, and Juneteenth represents that liberation. Why was it so easy to get this date made into a national holiday, yet it is still so hard for Black Americans to have their basic freedoms ensured?

Hi Friends!

Welcome to Issue 33 of this newsletter! Today we are focusing on Juneteenth, which just became national holiday this week. Juneteenth is an incredibly meaningful moment because enslaved people longed for freedom for generations, and Juneteenth represents that liberation. While many Black Americans have celebrated Juneteenth for their entire lifetime, there are definitely those that learned about this holiday later in life because it isn’t discussed in most curriculums and was not a national holiday. For most white Americans, Juneteenth is brand new. In this newsletter, I’ll discuss the history of Juneteenth, and encourage you to watch the clip below. I also want to encourage you to celebrate this holiday appropriately. This holiday may not be for you, and that’s okay. While it was so easy to pass it through senate and get Juneteenth approved on a national scale, it continues to be difficult for Black people to get their basic freedoms guaranteed. This Juneteenth is a great time to consider how you, as an ally, can help to achieve that. Let’s get into it!

Let’s Get Into It

A Brief History

Juneteenth marks the day when federal troops arrived in Galveston, Texas in 1865 to take control and ensure that all enslaved people be freed.

The Emancipation Proclamation was signed, after a very bloody civil war, in 1862 (over two years prior), making chattel slavery illegal, but the United States was still in a vulnerable position, with the south having succeeded, and President Lincoln’s policies had to be enforced through federal soldiers.

General Order No.3 lead to 4 million newly freed Black Americans and they found themselves a very hostile, racist society.

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor.” - General Order No.3

The military stepped in to ensure Black Americans received food, medical care and were protected from violence. When they left the south, it was a signal to southerners that the Federal Government would not protect the rights of Black people. Black folks were lynched and brutalized with impunity. There is still no anti-lynching law in America today.

There has always been constant, random, racist violence inflicted on Black people in this country and it continues today.

Juneteenth honors the end of slavery while also acknowledging that Black Americans continue to be marginalized and disenfranchised

This year, the senate unanimously passed a bill making Juneteenth a national holiday.

Juneteenth

As an ally to the Black community, Juneteenth should be a moment of reflection, contemplation, un-learning and reevaluating. Only 156 years ago troops marched into Texas. Still today, Black Americans are policed, villainized, disenfranchised and subjected to violence. Still today, schools around our nation are banned from teaching critical race theory. Still today, police benefit from qualified immunity, the same police who began as slave catchers. And today, jails will be closed on Juneteenth to celebrate its first year as a national holiday, as an overwhelming number of Black bodies sit in cages. So if this Juneteenth you have the day off of work, use it to amplify this message, to learn this history, to reflect on how a system that exploits Black humans has built your America.

As for my Black siblings this Juneteenth, you know what to do. Whatever you want. Whether that means kicking back at a family BBQ or taking a nap. It might mean showing up for a full day of work like you always do—since we know Black workers make up the largest percentage of front-line workers in America and will most likely not receive a day off on this national holiday. Feel however you want to feel, and do whatever you need to do this Juneteenth.

Next week, we wrap up June chatting about Pride Month and then circle back to our series on Stereotypes. I’ll see you there!

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

Stereotypes: 2

The Black Community: Let’s break down depictions originating during slavery, talk through some of the first portrayals of Black folks in pop culture and culminate with the ways Black people are described and represented in the news in connection to crime. There’s a lot to unpack here, and a lot more to learn outside of this newsletter.

Hi Friends!

Welcome to Issue 28 of this newsletter! Today we continue the conversation on Stereotypes more specifically, we will talk about stereotypes of the Black community. From portrayals in pop culture to depictions in newspapers, the way in which Black Americans are portrayed affects the way in which society at large views them. Let’s break down depictions originating during slavery, talk through some of the first portrayals of Black folks in pop culture and culminate with the ways Black people are described and represented in the news in connection to crime. There’s a lot to unpack here, and a lot more to learn outside of this newsletter. Let’s get into it!

Let’s Get Into It

Many of the Black characters we see in movies, books and TV shows are derived from old stereotypes founded during slavery and exaggerated through minstrel shows, where white men wore blackface and created caricatures of Black human beings. Let’s talk about some of these stereotypes, and as you read about them, think about how familiar some of these are. They’re often seen in pop culture today, and continue to reaffirm to society that they are accurate and realistic representations of Black people. Let’s unpack some of these concepts.

Archetypes Derived From Chattel Slavery

The Mammy figure represents Black women as mothers, caregivers, selfless servants and trustworthy nurturers. This figure depicted house slaves as overweight, dark-skinned and middle-aged. The Mammy was the right hand to the white mistress and loved by all. Historians believe this idea was created to discredit the very real narrative that most house slaves were young and lightskin and the frequent victims of rape by their masters. Mammy was created to desexualize Black women in the home. The Mammy caricature implied that Black women were only fit to be domestic workers; thus, the stereotype became a rationalization for economic discrimination. During slavery only the very wealthy could afford to purchase Black women and use them as house servants, but during Jim Crow even middle class white women could hire Black domestic workers. With this fictionalized women portrayed in pop culture and talked about for generations, white folks sought to create her in their homes. But unlike Aunt Jemima or Aunt Chloe, these were real Black women, denied opportunities for economic freedom, bearing slavery by another name.

The Uncle Tom stereotype derives from the book Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which was a pop culture depiction of an already established caricature of the time. Uncle Tom represents a Black man who is simple-minded and compliant but most essentially interested in the welfare of whites over that of other Blacks. Uncle Tom is often old, physically weak, psychologically dependent on whites for approval. White folks in the antebellum south upheld this figure as a loyal, religious, subservient character who, like The Mammy, was happy as slave and loved his master. During Black Lives Matter rallies, Black protestors called Black police officers Uncle Tom over riot shields and batons.

The Brute portrays Black men as innately savage, animalistic, destructive, and criminal -- deserving punishment, maybe death. Black Brutes are depicted as predators who target helpless victims, especially white women. Historically, proponents of slavery created and promoted images of Black folks that justified slavery and soothed white consciences, depicting Black people as docile, childlike, groveling, ignorant or harmless. More importantly, slaves were rarely depicted as Brutes because that portrayal might have become a self-fulfilling prophecy and slave owners wanted everyone to stay as calm and small as possible. During the Radical Reconstruction period (1867-1877), many white writers argued that without slavery -- which supposedly suppressed their animalistic tendencies -- Blacks were reverting to criminal savagery, and this is where the Brute stereotype begins. At the beginning of the twentieth century, much of the virulent, anti-black propaganda that found its way into scientific journals, local newspapers, and best-selling novels focused on the stereotype of the Black rapist. The claim that Black Brutes were, in epidemic numbers, raping white women became the public rationalization for the lynching of Black men.

The Angry Black Women or Sapphire with masculine features and dark skin, the hypersexual light-skinned Jezebel with Eurocentric features, the disrespectful and dimwitted Coon and childlike and ignorant Sambo, are all violent attacks on Black character, intelligence and virtue. I encourage you to explore these depictions more deeply, but for today’s newsletter, I want to dive deeper into how some of the archetypes above have translated to pop culture today.

Depictions in Pop Culture

Through this research I have been overwhelmed by the massive amount of stereotypes we see in modern pop culture. We see the crack head, pimp, drug dealer and prostitute, largely fueled by unfair media coverage and the emergence of reality shows like Cops, which disproportionately highlighted and televised Black and Brown criminals, though they make up a smaller percentage of the population and a smaller percentage of crimes than white people. We see the Welfare Queen who is a lazy Black women living off of the government, even though 43% of those on welfare are white, with 18% being Black. This trope is fueled by Linda Taylor, a mixed race women who became an infamous criminal for fraud as she was targeted by Ronald Reagan and more. We see Black people depicted as superhuman athletes more closely related to animals than humans, dominating sports because of breeding. Though the real reason why 75% of NBA players and 65% of NFL players are Black has more to do with societal expectations and the fact that many Black role models are rappers or athletes, while founding fathers, scientists, doctors and astronauts shown in school textbooks are almost exclusively white. There are too many tropes to unpack, but here are a few. What others have you learned?

The Black Brute stereotype was depicted for the world to see in The Birth of a Nation, a landmark of film history, as the first 12-reel film ever made and, at three hours, also the longest up to that point. A white man in blackface portrays a violent and dangerous rapist who terrorizes a white women. Just to be clear, in the most historic movie in cinematic technology, the first of its kind, we see a white man in blackface specifically and intentionally represent Black men as violent rapists. I want to continue unpacking the Brute stereotype as we ask about news coverage and portrayal.

Racial Bias in News Coverage

Have you ever heard the term Superpredator? John DiIulio, a professor at Princeton, coined the term in 1995. He predicted a coming wave of “superpredators”: “radically impulsive, brutally remorseless” “elementary school youngsters who pack guns instead of lunches” and “have absolutely no respect for human life.” As DiIulio and Fox themselves later admitted, the prediction of a juvenile superpredator epidemic turned out to be wrong. But after seeing Black men—since the first film ever created—being portrayed as violent criminals, it was easy for America to point to Black boys and label them as not just predators, but Superpredators. This rhetoric not only frightened white Americans, but made Black folks afraid of their Black neighbors.

In the 1970’s “The War on Drugs” was another war on young Black men. Nixon’s policy chief said, “We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or Black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and Blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities.”

In today’s media, the news portrays that 72% of assaults are perpetrated by Black people, while in reality it is closer to 49%. On New York’s local news, 80% of theft discussed on the news is committed by Black people, while theft by Black folks accounts for approximately 55% of the NYPD’s arrests.

Black men comprise about 13% of the male population, but about 35% of those incarcerated. 1 in 3 black men born today can expect to be incarcerated in his lifetime, compared to 1 in 6 Latino men and 1 in 17 white men. Black women are similarly impacted: 1 in 18 Black women born in 2001 is likely to be incarcerated sometime in her life, compared to 1 in 111 white women.

Do you remember the Black Brute? Dangerous. Frightening. Criminal. Does this seem familiar?

There are so many more stereotypes perpetuated by the news, by societal expectations, by pop culture and within our own biases. This week’s newsletter is just a starting point. What do you think of when you think of a Black man or Black women or Black child or Black person? What stereotypes are you believing and perpetuating? Do you see the thread that connects the desires of white supremacy to the depictions of Black human beings? Take a moment and think about what you just read and how you can use it to fuel some new interactions and perceptions in your day to day life.

Next week, we dive into stereotypes around the Latinx community. See ya there.

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

George Floyd

I want to take this opportunity to pause and reflect on George Floyd’s life — a life he wanted to live, deserved to live, and was supposed to live. George Floyd was not a martyr. He was a father. He was a son. He was a brother. He was a partner. He was a human being deserving of dignity and respect. Derek Chauvin’s conviction represents accountability for the crime he committed, but it falls short of justice. Justice would be George Floyd’s life and not his death.

Hello Friends,

On Tuesday, April 20, Derek Chauvin was found guilty of the murder of George Floyd.

I want to take this opportunity to pause and reflect on George Floyd’s life — a life he wanted to live, deserved to live, and was supposed to live. I wish that we as a society were moved to action simply by witnessing the everyday trauma that is being a marginalized person in America and not because we watched a man call out for his mother and have the life drain from his body under the knee of white supremacy. George Floyd was not a martyr. He was a father. He was a son. He was a brother. He was a partner. He was a human being deserving of dignity and respect. Derek Chauvin’s conviction represents accountability for the crime he committed, but it falls short of justice. Justice would be George Floyd’s life and not his death.

Last week we mourned 20-year-old Daunte Wright who was murdered at a traffic stop in Minneapolis, only a few miles from where George Floyd took his last breath. Soon after, we mourned Adam Toledo, the seventh grader who was shot in the chest by Chicago Police. Moments before Tuesday’s verdict was read, 16-year-old Ma'Khia Bryant died at the hands of a Columbus police officer. While writing this, I learned about Andrew Brown of North Carolina, a father of ten who was murdered by police.

White people who are heavily armed, visibly dangerous, and unequivocally guilty are apprehended and arrested without issue. Why are Black and Brown human beings not given the same treatment? We know the answer is racism, and the reason you’re here, reading this newsletter, is because you wonder what you can do to combat it.

After a year of writing out three point action steps, and hyperlinking charities, and selling tickets for workshops, I know (and you know) that the answer to combating white supremacy is more arduous and more challenging than reading a book, or following a color coded list. The work is lifelong. It took 400 years to establish this society and it will take time to unravel its web of bias and privilege.

I am tired, but not hopeless. I am devastated, but not despondent. I believe in a future without endless waves of tragedy and injustice drowning those that are most vulnerable.

Today, I don’t ask you to watch a video or take a survey or sign a petition, but to sit with yourself and shine a light on the darkest corners of yourself. To question your efforts. To question your biases. To question your motives. To imagine a world where you do nothing more than eradicate racism from your own mind, from your own home, from your own community.

The learning and the donating and the uplifting never stop. Buying from Black-owned businesses and ordering books from Black authors, signing petitions to relinquish Indigenous lands and writing letters to abolish ICE, uplifting Black and Brown leaders and paying for Patreons and workshops and events — these things matter. But take a look inside. Take a moment to think about who you are and who you want to be.

I am tired, but not hopeless.

Continue. I know I will.

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

Black American Sign Language

Black American Sign Language (BASL) or Black Sign Variation (BSV) is a dialect of American Sign Language (ASL) used most commonly by deaf Black Americans in the United States. The divergence from ASL was influenced largely by the segregation of schools in the South.

“The difference between BASL and ASL is that BASL got seasoning.”

Hi Friends!

Welcome to Issue 24 of this newsletter! Today’s topic is Black American Sign Language (BASL). Like many, I saw Nakia Smith’s (@itscharmay) viral videos about BASL on TikTok. I knew right away that I wanted to dig in and learn more. Black American Sign Language (BASL) or Black Sign Variation (BSV) is a dialect of American Sign Language (ASL) used most commonly by deaf Black Americans in the United States. The divergence from ASL was influenced largely by the segregation of schools in the South. Let’s go through a brief history and then I’ll share some resources and folks that I am learning from. This is definitely a topic that I will be continuing to learn more about, so if you have anything to add to this week’s blog post, let me know! Let’s get into it!

Key Terms

Black American Sign Language: Black American Sign Language (BASL) or Black Sign Variation (BSV) is a dialect of American Sign Language (ASL) used most commonly by deaf Black Americans in the United States.

American Sign Language: American Sign Language (ASL) is a complete, natural language that has the same linguistic properties as spoken languages, with grammar that differs from English. ASL is expressed by movements of the hands and face. There is no universal sign language. Different sign languages are used in different countries or regions.

deaf (Lowercase “d”): The word deaf is used to describe or identify anyone who has a severe hearing problem. Sometimes it is used to refer to people who are severely hard of hearing too.

Deaf (Uppercase “D”): Folks use Deaf with a capital D to refer to people who have been deaf all their lives, or since before they started to learn to talk. They are pre-lingually deaf. It is an important distinction, because Deaf people tend to communicate in sign language as their first language. For most Deaf people English is a second language.

Oralism: Places less emphasis on signing and more emphasis on teaching deaf students to speak and lip-read.

Ableism: Ableism is the discrimination of and social prejudice against people with disabilities based on the belief that typical abilities are superior. At its heart, ableism is rooted in the assumption that disabled people require ‘fixing’ and defines people by their disability. Like racism and sexism, ableism classifies entire groups of people as ‘less than,’ and includes harmful stereotypes, misconceptions, and generalizations of people with disabilities. Being deaf is considered a disability under the ADA.

Let’s Get Into It

A Brief History

Schools for Black deaf children in the United States began to emerge after the Civil War. The first permanent school for the deaf in the United States, which later came to be known as the American School for the Deaf, opened in 1817 in Hartford, Conn. The school enrolled its first Black student in 1825.

Segregation in the South in 1865 played a large role in Black ASL’s development.

Separation led to Black deaf schools’ differing immensely from their white counterparts. White schools tended to focus on an oral method of learning and provide an academic-based curriculum, while Black schools emphasized signing and offered vocational training.

In the 1870s and 1880s, white deaf schools moved toward oralism — which places less emphasis on signing and more emphasis on teaching deaf students to speak and lip-read. Because the education of white children was privileged over that of Black children, oralism was not as strictly applied to the Black deaf students. Oralist methods often forbade the use of sign language, so Black deaf students had more opportunities to use ASL than did their white peers.

The last Southern state to create an institution for Black deaf children was Louisiana in 1938. Black deaf children became a language community isolated from white deaf children, with different means of language socialization, allowing for different dialects to develop.

As schools began to integrate, students and teachers noticed differences in the way Black students and white students signed. Carolyn McCaskill, now professor of ASL and Deaf Studies at Gallaudet University, recalls the challenge of understanding the dialect of ASL used by her white principal and teachers after her segregated school of her youth integrated: “Even though they were signing, I didn’t understand,” she said. “And I didn’t understand why I didn’t understand.”

With the pandemic forcing many to flock to virtual social spaces, Isidore Niyongabo, president of National Black Deaf Advocates, said he had seen online interaction grow within his organization and across the Black deaf community as a whole. “We are starting to see an uptick with the recognition of the Black deaf culture within America,” Mr. Niyongabo said, adding that he expected it would “continue spreading throughout the world.”

Facts & Figures

Several scholars say that Black ASL is actually more aligned with early American Sign Language than contemporary ASL, which was influenced by French sign language.

Compare ASL with Black ASL and there are notable differences: Black ASL users tend to use more two-handed signs, and they often place signs around the forehead area, rather than lower on the body.

About 11 million Americans consider themselves deaf or hard of hearing, according to the Census Bureau’s 2011 American Community Survey, and Black people make up nearly 8 percent of that population.

From Nakia Smith

In her interview with the New York Times, Nakia (@itscharmay) talks about code switching, but with sign language. When she attended a school that consisted of primarily hearing students, she says: “I started to sign like other deaf students that don’t have deaf family,” said Ms. Smith, whose family has had deaf relatives in four of the last five generations. “I became good friends with them and signed like how they signed so they could feel comfortable.”

Viral Video With Her Grandfather

Viral Video With Her Grandparents

Resources

This is really my first week ever learning about BASL, so I am definitely no expert, but I hope you’re just as excited to learn as I am. Above are a bunch of great resources, as well as linked throughout this post. Let’s keep learning from folks that practice BASL and experts in that community. Next week, we’re talking about Lateral Oppression which occurs within marginalized groups where members strike out at each other as a result of being oppressed. I’ll see ya there!

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

Mental Health in the Black Community

I decided to turn this into a series on mental health in BIPOC communities. BIPOC refers to Black, Indigenous or people of color. And while this term does have some controversy around inclusivity and specificity, I think it applies here. This week, we will dive into Mental Health in the Black Community. From generational trauma to historical trauma to coping mechanisms and stigmas, there is a lot to dive in to.

Hi Friends!

Welcome to Issue 18 of this newsletter! I decided to turn this into a series on mental health in BIPOC communities. BIPOC refers to Black, Indigenous or people of color. And while this term does have some controversy around inclusivity and specificity, I think it applies here. This week, we will focus on Mental Health in the Black Community. From generational trauma to coping mechanisms and stigmas, there is a lot to dive in to. Let’s get into it!

Key Terms

Generational Trauma: This is trauma that isn’t just experienced by one person but extends from one generation to the next. In 1966, Canadian psychiatrist Vivian M. Rakoff, MD, and her colleagues recorded high rates of psychological distress among children of Holocaust survivors, and the concept of generational trauma was first recognized. Trauma affects genetic processes, leading to traumatic reactivity being heightened in populations who experience a great deal of trauma.

Sterilization: A process or act that renders an individual incapable of sexual reproduction. Forced sterilization occurs when a person is sterilized after expressly refusing the procedure, without her knowledge or is not given an opportunity to provide consent.

Lobotomy: Lobotomy was an umbrella term for a series of different operations that purposely damaged brain tissue in order to treat mental illness. It is is a neurosurgical operation that involves severing connections in the brain's prefrontal lobe.

Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome: P.T.S.S. is a theory that explains the etiology of many of the adaptive survival behaviors in African American communities throughout the United States and the Diaspora. It is a condition that exists as a consequence of multigenerational oppression of Africans and their descendants resulting from centuries of chattel slavery. A form of slavery which was predicated on the belief that African Americans were inherently/genetically inferior to whites. This was then followed by institutionalized racism which continues to perpetuate injury.

Let’s Get Into It

A Brief History

In 1848 John Galt, a physician and medical director of the Eastern Lunatic Asylum in Williamsburg, Virginia, offered that “blacks are immune to mental illness.” Galt hypothesized that enslaved Africans could not develop mental illness because as enslaved people, they did not own property, engage in commerce, or participate in civic affairs such as voting or holding office. According to Galt and others at that time, the risk of “lunacy” would be highest in those populations who were emotionally exposed to the stress of profit making, principally wealthy white men.

Dr. Benjamin Rush diagnosed Negritude which he described as the irrational desire by Blacks to become white.

Dr. Samuel Cartwright, a pro-slavery physician diagnosed Drapetomania, a disease that caused enslaved blacks to flee their plantations and Dysaethesia Aethiopia, a disease that purportedly caused a state of dullness and lethargy, which would now be considered depression. He argued that severe whipping was the typically the best “treatment” for both conditions.

Most pre-Civil War mental health facilities in the South usually barred the enslaved for treatment. Apparently mental health experts believed that housing Blacks and whites in the same facilities would detrimentally affect the healing of the whites.

In 1895, Dr. T.O. Powell, the superintendent of the Georgia Lunatic Asylum observed an increase in insanity and consumption (tuberculosis) among Black people which he attributed to three decades of freedom. He argued that when the former slaves got their freedom, it caused them to have little or no control over their appetites and passions and thus led to a rise in insanity.

In the 1930s Black Americans diagnosed as insane were the most widely sterilized group. Although sterilization lost some of its appeal when it was discovered Nazi Germany embraced the practice on a wide scale, by the 1970s some states in the South, including notably North Carolina and Alabama. In North Carolina in the 1960s, for example, more than 85% of those legally sterilized were Black women.

Black Americans were victims of lobotomies from the 1930s to the 1960s.Dr. Frank Ervin, a psychiatrist, and two neurosurgeons, Drs. Vernon Mark and William Sweet ignored the systematic oppression, poverty, discrimination, and police brutality of the 1960s and argued that this violence was the result of a surgically-treatable brain disorder and promoted their agenda as a specific contribution to ending the political unrest of the period. While never widely accepted and practiced, some lobotomies were performed on Black children as young as five years old who exhibited aggressive or hyperactive behaviors.

Today, Black Americans have a distrust of the medical system due to historical abuses of Black people in the guise of health care, less access to adequate insurance, culturally responsive mental health providers, financial burden, and past history with discrimination in the mental health system. (Columbia)

Generational Trauma

A growing body of research suggests that traumatic experiences can cause profound biological changes in the person experiencing the traumatic event. Cutting edge researchers are also beginning to understand how these physiological changes are genetically encoded and passed down to future generations. (Columbia)

Watch this 5 minute video for some truly amazing insight to generational trauma and what Dr. Joy DeGruy calls Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome.

Stigma

Instead of seeking mental health care, useful strategies including religious coping and methods such as pastoral guidance and prayer often are the most preferred coping mechanism in the Black community. These ideas often lead people to believe that a mental health condition is a personal weakness due to negative stereotypes of instability and attitudes of rejection. Individuals may be more likely to believe that since they’ve survived so much adversity, they’re strong—and no one has a right to tell them that there is something wrong with them. (Columbia)

Due to a reasonable distrust of the medical system stemming from all of the past history discussed earlier, the church was consistently a place to go when there was nowhere else for Black people to seek refuge. Moreover, given that the Black community exists at the intersection of racism, classism, and health inequity, their mental health needs are often exacerbated and mostly unfulfilled. (Columbia)

The Black community, in particular, is at significantly increased risk of developing a mental health issue due to historical, economic, social, political influences that systemically expose the Black community to factors known to be damaging to psychological and physical health. Research consistently shows that these disparities are not a new phenomenon and have been present for generations. (Columbia)

Facts & Figures

25% of African Americans seek mental health care, compared to 40% of whites. (McLean)

The adult Black community is 20% more likely to experience serious mental health problems, such as Major Depressive Disorder or Generalized Anxiety Disorder than their white counterparts. (McLean)

The Black community comprises approximately 40% of the homeless population, 50% of the prison population, and 45% of children in the foster care system. (McLean)

Only 1 in 3 Black Americans who could benefit from mental health treatment receive it. (McLean)

Black individuals are less frequently included in research, which means their experiences with symptoms or treatments are less likely to be taken into consideration. (McLean)

They’re also more likely to go to the emergency room or talk to their primary care physician when they’re experiencing mental health issues, rather than seeing a mental health professional. (McLean)

Black individuals are also more likely to be misdiagnosed by treatment providers. This can fuel the distrust toward mental health professionals as a misdiagnosis can lead to poor treatment outcomes. (McLean)

Black individuals are more likely to have involuntary treatment, whether it is forced inpatient or outpatient treatment. This contributes to the stigma, hostility, and lack of willingness to voluntarily seek care. (McLean)

In the 1990s, a public opinion poll found that 63% of African Americans believed depression was a personal weakness and only 31% believed it was a health problem. (McLean)

Today suicide rates in African American children aged 5-11 years have increased steadily since the 1980s and are now double those of their Caucasian counterparts.

Action Steps

Bring awareness to the use of stigmatizing language around mental illness

Educate family, friends, and colleagues about the unique challenges of mental illness within the Black community

Become aware of our own attitudes and beliefs to reduce implicit bias and negative assumptions

Rescources

Through their partnerships with Therapy for Black Girls, National Queer & Trans Therapists of Color Network, Talkspace and Open Path Collective, Loveland Therapy Fund recipients have access to a comprehensive list of mental health professionals across the country providing high quality, culturally competent services to Black women and girls.

Next week, we continue to talk about the history, trauma and stigma that plagues people of color when it comes to seeking and being adequately treated for mental health concerns. Personally, I’ve been very transparent about my mental health care, and feel like psychotherapy has been a fundamental part to my processing, healing and growing through both personal and generational trauma. I’ll see you next week to talk about Mental Health in the Indigenous Community.

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

Defund the Police: What Does That Mean?

You might have heard the phrase “defund the police” on social media and news outlets a lot lately. Do you know what it means? Can you imagine what it might look like? Defund the police means, in short, divest in the police force, invest in the community, something that benefits everyone.

Hello Friends!

Welcome to Issue 2 of this newsletter! This week’ topic is Defending the Police: What Does That Mean? This Phrase has been permitting social media and news outlets over the last week or so, let’s take a closer look.

Also— Juneteenth is coming up this Friday. “What’s Juneteenth?” Honey, I am going to tell you. Keep scrolling on down and let’s get into it.

Key Terms

Qualified Immunity: Shields police from lawsuits

Defund: Prevent from continuing to receive funds

Abolish: Formally put an end to a system, practice or institution

Reform: Make changes in an institution in order to improve it

Let’s Get Into It

There are a million articles you can read on this, but let’s break down the main points. I‘ll also link my sources below if you want to delve a little deeper.

Defund The Police

Reducing police budgets and reallocating those fund to social services like education, healthcare, housing, youth services and resources to support the community.

Police departments are tasked with maintaining order in society; however, they are often calling in response to situations that social services (healthcare, housing, youth development, etc) are better equipped to handle. We could invest in social services and send specialists like social workers, violence interrupters and mental health practitioners to address non-criminal issues more effectively.

Facts And Figures

In a fiscal year, 2020 New York City’s expenses for the New York City Police Department will total $10.9 billion (CNBC)

LA’s proposed police budget fro 2021 is $1.8 billion, which is more than half of the city’s total spending for the year. (The Cut)

The United States has less than 5% of the world’s population, yet we have almost 25% of the world’s total prison population. (Washington Post)

According to the bureau of justice statistics, the annual cost of mass incarceration in the United States is $81 billion dollars. (EJI)

What Is Juneteenth?

Juneteenth is the oldest nationally celebrated commemoration of the ending of slavery in the United States.

Celebrate it with the color red which symbolizes perseverance. Strawberry soda, red velvet cake, strawberries, red beans and rice and watermelon.

Next week, we are focusing on how to support the Black LGBTQ+ community. Remember, ALL Black lives matter—trans*, disabled, queer, straight, cisgendered, able-bodied, all of them. Next week we delve a little deeper. See you there!

Resources

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

Black Lives Matter

Welcome to my new weekly newsletter, bringing together my Fitness Activism work and education to support the social and civic reckoning shifting America.

“Change will not come if we wait for some other person, or if we wait for some other time. We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change that we seek.”

Hello Friends!

Last week I decided to transition this weekly newsletter on fitness to a weekly newsletter in support of the Black Lives Matter movement. As a Black person in America, it feels important for me to use my voice now more than ever. If you're new to my IG or boxing classes, welcome welcome welcome.

My goal for this newsletter is to break down smaller topics and offer action steps and resources to really get sh*t down. This week is just an intro with some background resources on being a good ally and just beginning to understand systemic racism. Continue reaching out to me on social media and via email, I love to hear from you guys,and on that note, let’s get into it!

Whatever you're good at (for me it’s fitness and talking and graphic design) use that to start making positive change. We can’t all do everything and everyone’s contribution is valuable. Because of this mindset, I turned all of my digital classes into a safe space to hold conversations on blackness and racism and all of my fitness newsletters into, well, this!

Every week we will delve deeper on specific topics and issues. To start us off, here are some of my favorite resources, videos, articles and the organizations I have been donating too. Check them out.

Resources

Check out some tips on communication from Rachel Cargle below:

1. Yes/But also known as “whataboutism” , is a variant of the “tu quoque” logical fallacy that attempts to discredit an opponent's position by charging them with hypocrisy without directly refuting or disproving their argument. (source: Zimmer, Ben. WSJ, 2017 ).

Every week, new topics, new talks, new action steps, new organizations. This is the first of many newsletters. I am so excited to get specific on ways to make real change. See you there!