Weekly Anti-racism NewsletteR

Because it ain’t a trend, honey.

-

Taylor started her newsletter in 2020 and has been the sole author of almost one hundred blog mosts and almost two hundred weekly emails. A lifelong lover of learning, Taylor began researching topics of interest around anti-racism education and in a personal effort to learn more about all marginalized groups. When friends asked her to share her learnings, she started sending brief email synopsises with links to her favorite resources or summarizing her thoughts on social media. As the demand grew, she made a formal platform to gather all of her thoughts and share them with her community. After accumulating thousands of subscribers and writing across almost one hundred topics, Taylor pivoted from weekly newsletters to starting a podcast entitled On the Outside. Follow along with the podcast to learn more.

-

This newsletter covers topics from prison reform to colorism to supporting the LGBTQ+ community. Originally, this was solely a newsletter focused on anti-racism education, but soon, Taylor felt profoundly obligated to learn and share about all marginalized communities. Taylor seeks guidance from those personally affected by many of the topics she writes about, while always acknowledging the ways in which her own privilege shows up.

Affirmative Action: Part 1

Today, June 29, the Supreme Court struck down college affirmative action programs. This week’s topic: Affirmative Action . A conservative supermajority in the Supreme Court upending decades of jurisprudence when they decided that race-conscious admissions programs at Harvard and the University of North Carolina are unconstitutional. This decision has many implications, including the potential to change the way that college admission processes are handled, and the potential to have a ripple effect that impacts the business world and corporate sector.

Hi Friends,

Welcome to Issue 55 of this newsletter. Today, June 29, the Supreme Court struck down college affirmative action programs. This week’s topic: Affirmative Action . A conservative supermajority in the Supreme Court upending decades of jurisprudence when they decided that race-conscious admissions programs at Harvard and the University of North Carolina are unconstitutional. This decision has many implications, including the potential to change the way that college admission processes are handled, and the potential to have a ripple effect that impacts the business world and corporate sector. The two cases were brought by Students for Fair Admissions, a group founded by Edward Blum. Blum is not a lawyer. According to a New York Times profile, “he is a one-man legal factory with a growing record of finding plaintiffs who match his causes, winning big victories and trying above all to erase racial preferences from American life”. He has orchestrated more than two dozen lawsuits challenging affirmative action practices and voting rights laws across the country. Rachel Kleinman, senior counsel at the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, said that Mr. Blum’s opposition to affirmative action was related to “this fear of white people that their privilege is being taken away from them and given to somebody else who they see as less deserving.” At its core, affirmative action is not the practice of giving Black and Latinx students priority during college admission. While people like Edward Blum ignore the historical backdrop of the American experience and reduce establish policies to feelings over facts, today we will learn the truth about what affirmative action really is, how it came to be, and why it has been an important—albeit imperfect—part of the admissions process.

After beginning to research the history and impact of affirmative action, I’ve decided to divide this newsletter into two. Today, we will discuss the history and background of affirmative action. Next time, we will discuss the impact and implications of affirmative action and the most recent Supreme Court decision. Let’s get into it.

Key Words

“Strict Scrutiny” : The Court calls for "strict scrutiny" in determining whether discrimination existed before implementing a federal affirmative action program. "Strict scrutiny" meant that affirmative action programs fulfilled a "compelling governmental interest," and were "narrowly tailored" to fit the particular situation. To pass the strict scrutiny test, a law must be narrowly tailored to serve a compelling government interest. The same test applies whether the racial classification aims to benefit or harm a racial group. Strict scrutiny also applies whether or not race is the only criteria used to classify.

“Race Neutral”: “Race neutral” does not appear in the opinion of the court, written by Chief Justice John Roberts, which states that colleges and universities have “concluded, wrongly, that the touchstone of an individual’s identity is not challenges bested, skills built, or lessons learned but the color of their skin.” But when Roberts clarifies that students can still refer to their race in admissions essays, explaining challenges they’ve overcome, he and the majority are buying into the idea of race neutrality. Justice Clarence Thomas, who wrote his own concurring opinion, uses the term “race neutral” repeatedly, offering it as an antidote to affirmative action.

Supreme Court Opinion: The term “opinions” refers to several types of writing by the Justices. The most well-known opinions are those released or announced in cases in which the Court has heard oral argument. Each opinion sets out the Court’s judgment and its reasoning and may include the majority or principal opinion as well as any concurring or dissenting opinions.

Executive Order: An executive order is a signed, written, and published directive from the President of the United States that manages operations of the federal government. They are numbered consecutively, so executive orders may be referenced by their assigned number, or their topic.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964: The Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin. Provisions of this civil rights act forbade discrimination on the basis of sex, as well as, race in hiring, promoting, and firing. The Act prohibited discrimination in public accommodations and federally funded programs. It also strengthened the enforcement of voting rights and the desegregation of schools.

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act: As amended, Title VII protects employees and job applicants from employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex and national origin.

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission: The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) is responsible for enforcing federal laws that make it illegal to discriminate against a job applicant or an employee because of the person's race, color, religion, sex (including pregnancy and related conditions, gender identity, and sexual orientation), national origin, age (40 or older), disability or genetic information. Most employers with at least 15 employees are covered by EEOC laws (20 employees in age discrimination cases). Most labor unions and employment agencies are also covered. The laws apply to all types of work situations, including hiring, firing, promotions, harassment, training, wages, and benefits.

Equal Protection Clause: The Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment ensures that all Americans receive equal protection under the Constitution. Both the majority and the minority opinions in Thursday’s ruling cited the clause, using different interpretations. Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. wrote that race-based admissions programs “cannot be reconciled with the guarantees of the Equal Protection Clause,” while Sonia Sotomayor wrote in a dissent that the decision “subverts the constitutional guarantee of equal protection by further entrenching racial inequality in education.”

Lets Get Into It

Affirmative action, as a term, came to the fore in 1935 with the Wagner Act, a federal law that gave workers the right to form and join unions. But John F. Kennedy was the first president to link the term specifically with a policy meant to advance racial equality, according to Smithsonian Magazine.

On March 6, 1961 President John F. Kennedy issued Executive Order 10925, which included a provision that government contractors "take affirmative action to ensure that applicants are employed, and employees are treated during employment, without regard to their race, creed, color, or national origin." The intent of this executive order was to affirm the government's commitment to equal opportunity for all qualified persons, and to take positive action to strengthen efforts to realize true equal opportunity for all. This executive order was superseded by Executive Order 11246 in 1965.

So, where exactly are we in history in 1961 when it comes to the rights of Black Americans?

The 13th Amendment abolished slavery in 1865, 96 years prior

To put this in context, if a Black American lived to be around 100, they would have lived through being a slave and also been alive when President John F. Kennedy issued Executive Order 10925. Most Black Americans at this time would have parents and grandparents who were slaves when President John F. Kennedy issued Executive Order 10925.

The first “Jim Crow Law” is passed in Tennessee mandating the separation of African Americans from whites on trains in 1870, 91 years prior

Plessy v. Ferguson established the “separate but equal” doctrine that allows segregation, discrimination and racism to flourish in 1896, 65 years prior

Jackie Robinson became the first Black American in the twentieth century to play baseball in the major leagues in 1947, 14 years prior

Brown v. Board of education which desegregated public schools was in 1954, 7 years prior

Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott took place in 1955, 6 years prior

The Civil Rights Act, which extended civil, political, and legal rights and protections to Black Americans, including former slaves and their descendants, and put an end segregation in public and private facilities was in 1964, 3 years after

The Voting Rights Act, which allowed all Americans access to the polls was in 1965, 4 years after

Martin Luther King Jr was assassinated in 1968, 7 years after

The History of Affirmative Action

1961: The first use of the term “affirmative action” specifically with a policy meant to advance racial equality is in Executive Order 10925, as discussed above.

1961: The “Plan for Progress” is signed by Vice President Johnson and Courtlandt Gross, the president of Lockheed

NAACP labor secretary Herbert Hill filed complaints against the hiring and promoting practices of Lockheed Aircraft Corporation. Lockheed was doing business with the Defense Department on the first billion-dollar contract. Due to taxpayer-funding being 90% of Lockheed's business, along with disproportionate hiring practices, Black workers charged Lockheed with "overt discrimination." Lockheed signed an agreement with Vice President Johnson that pledged an "aggressive seeking out for more qualified minority candidates for technical and skill positions.” Soon, other defense contractors signed similar voluntary agreements. However, most corporations in the south, still ruled by Jim Crow Laws, ignored the recommendations.

1964: The Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin.

Note that this same act was used to continue discrimination. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 had limited the type of remedies possible by forbidding any form of discrimination. This was interpreted to include preferential hiring, which was seen as compensatory discrimination. To put it plainly — folks found a way to reason that giving Black workers preferential treatment by hiring them with an emphasis on their race could be considered discriminatory in and of itself.

1964: The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) was created by Congress in 1964 to enforce Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, as amended, protects employees and job applicants from employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex and national origin.

1965: President Lyndon B. Johnson issued Executive Order 11246, prohibiting employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, and national origin by those organizations receiving federal contracts and subcontracts. This executive order requires federal contractors to take affirmative action to promote the full realization of equal opportunity for women and minorities. The Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs (OFCCP), under the Department of Labor, monitors this requirement for all federal contractors, including all UC campuses. Compliance with these regulations (for ederal contractors employing more than 50 people and having federal contracts totaling more than $50,000) includes disseminating and enforcing a nondiscrimination policy, establishing a written affirmative action plan and placement goals for women and minorities, and implementing action-oriented programs for accomplishing these goals.

1967: President Johnson amended Executive Order 11246 to also include sex.

“The contractor will not discriminate against any employee or applicant for employment because of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. The contractor will take affirmative action to ensure that applicants are employed, and that employees are treated during employment, without regard to their race, color, religion, sex or national origin. Such action shall include, but not be limited to the following: employment, upgrading, demotion, or transfer; recruitment or recruitment advertising; layoff or termination; rates of pay or other forms of compensation; and selection for training, including apprenticeship.”

1969: The Philadelphia Plan was implemented by Richard Nixon. For the first time, a specific industry was required to articulate a plan for hiring minority workers. The Nixon administration created specific hiring goals in the highly segregated construction industry. The Philadelphia Plan required Philadelphia government contractors in six construction trades to set goals and timetables for the hiring of minority workers or risk losing the valuable contracts. No quotas were set. This left businesses a fair amount of autonomy in determining how to meet the goals. As a result, the Philadelphia Plan withstood a court challenge and growing public hostility to affirmative action.

1969: Colleges voluntarily adopted similar policies to combat racial discrimination. In 1969, many elite universities admitted more than twice as many Black students as they had the year before. This change was directly linked to the civil rights movement. With civil rights activists urging schools to admit more Black applicants, colleges responded. Higher education had been almost exclusively white for most of its history, but a growing number of universities were now crafting affirmative action policies in an effort to expand access to higher education.

1974: Marco DeFunis Jr. v. Odegaard — Marco DeFunis, a white man, argued that he was denied admission to the University of Washington Law School because the school had prioritized admitting minority students who were less qualified, saying that this violated the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause. By the time the United States Supreme Court considered the case, DeFunis was already in his last year of law school and the court ruled that the case was moot. Though the court chose not to address the issues within the case, it was the first case heard on affirmative action since the policy was established in the 1960s.

1978: Regents of the University of California v. Bakke — Alan Bakke was rejected twice from the medical school at the University of California, Davis. Mr. Bakke, who is white, argued that the school’s affirmative action policy to reserve 16 out of 100 spots for qualified minority students violated the equal protection clause as well as the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The Supreme Court ruled that the racial quota system used by the university did violate the Civil Rights Act and that Mr. Bakke should be admitted. Justice Lewis F. Powell acknowledged in his opinion that a state had legitimate interests in considering the race of applicants, and that a diverse student body could provide compelling educational benefits. The case established the court’s position on affirmative action for decades. A state university had to meet a standard of judicial review known as strict scrutiny: Race could be a narrowly tailored factor in admissions policies. Racial quotas, however, went too far.

1980: Fullilove v. Klutznick —While Bakke struck down strict quotas, in Fullilove the Supreme Court ruled that some modest quotas were perfectly constitutional. The Court upheld a federal law requiring that 15% of funds for public works be set aside for qualified minority contractors. The "narrowed focus and limited extent" of the affirmative action program did not violate the equal rights of non-minority contractors, according to the Court—there was no "allocation of federal funds according to inflexible percentages solely based on race or ethnicity."

1983: Reagan signed Executive Order 12432. The executive order requires that each federal agency with grant making capabilities establish an Annual Minority Business Development Plan with the stated goal to increase minority business participation. Agencies are expected to establish programs that assist minority business enterprises to procure contracts and manage those contracts awarded. As a stipulation of the executive order, the progress toward these goals is to be annually reported to the Secretary of Commerce. While the Reagan administration opposed discriminatory practices, it did not support the implementation of quotas and goals and did not support Executive Order 11246. Bi-partisan opposition in Congress and other government officials blocked the repeal of Executive Order 11246 but he reduced funding for the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, arguing that "reverse discrimination" resulted from these policies.

1997: Proposition 209 was enacted in California, which is a state ban on all forms of affirmative action: "The state shall not discriminate against, or grant preferential treatment to, any individual or group on the basis of race, sex, color, ethnicity, or national origin in the operation of public employment, public education, or public contracting." Proposed in 1996, the controversial ban had been delayed in the courts for almost a year before it went into effect. Over the past three decades, 10 states have banned affirmative action in college admissions. And in many cases, voters approved those bans.

1998: Washington becomes the second state to abolish state affirmative action measures when it passed "I 200," which is similar to California's Proposition 209.

2000: Florida legislature approves education component of Gov. Jeb Bush's "One Florida" initiative, aimed at ending affirmative action in the state.

2003: Grutter v. Bollinger — Barbara Grutter, a white woman who was denied admission to the University of Michigan Law School, said that the school had used race as a predominant factor for admitting students. When the case reached the Supreme Court, a 5-4 opinion led by Justice Sandra Day O’Connor upheld the Bakke decision. The Court ruled that each admissions decision is based on multiple factors, and that the school could fairly use race as one of them. The case reaffirmed the court’s position that diversity on campus is a compelling state interest.

2003: Gratz v. Bollinger — Though decided on the same day and focused on the same university, the Gratz case and Grutter case had different outcomes. Jennifer Gratz and Patrick Hamacher, both white, were denied admission to the University of Michigan. They argued that a point system in use by the admissions office beginning in 1998 was unconstitutional. Students who were part of an underrepresented minority group automatically received 20 points in a system that required 100 points for admittance, which meant that nearly every applicant of an underrepresented minority group was admitted. In a 6-3 opinion led by Justice William H. Rehnquist, the Supreme Court ruled that the point system did not meet the standards of strict scrutiny established in previous cases. The Grutter and Gratz cases provided a blueprint for how schools could use race as a factor in admissions policies. The Court held that the OUA’s policies were not sufficiently narrowly tailored to meet the strict scrutiny standard. Because the policy did not provide individual consideration, but rather resulted in the admission of nearly every applicant of “underrepresented minority” status, it was not narrowly tailored in the manner required by previous jurisprudence on the issue.

2006: Meredith v. Jefferson — Jefferson County Public Schools (JCPS) were integrated by court order until 2000. After its release from the order, JCPS implemented an enrollment plan to maintain substantial racial integration. Students were given a choice of schools, but not all schools could accommodate all applicants. In those cases, student enrollment was decided on the basis of several factors, including place of residence, school capacity, and random chance, as well as race. However, no school was allowed to have an enrollment of black students less than 15% or greater than 50% of its student population. The District Court ruled that the plan was constitutional because the school had a compelling interest in maintaining racial diversity.

2006: Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1 — The Seattle School District allowed students to apply to any high school in the District. Since certain schools often became oversubscribed when too many students chose them as their first choice, the District used a system of tiebreakers to decide which students would be admitted to the popular schools. The second most important tiebreaker was a racial factor intended to maintain racial diversity. At a particular school either whites or non-whites could be favored for admission depending on which race would bring the racial balance closer to the goal. A non-profit group, Parents Involved in Community Schools (Parents), sued the District, arguing that the racial tiebreaker violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment as well as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Washington state law. A federal District Court dismissed the suit, upholding the tiebreaker. On appeal, a three-judge panel the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit reversed. By a 5-4 vote, the Court applied a "strict scrutiny" framework and found the District's racial tiebreaker plan unconstitutional under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. This was a major setback for affirmative action.

2016: Fisher v. University of Texas (Two Cases) — Abigail Fisher, a white woman who was rejected from the University of Texas, said that the school’s two-part admissions system, which takes race into consideration, is unconstitutional. The university first admits roughly the top 10 percent of every in-state graduating high school class, a policy known as the Top Ten Percent Plan, and then reviews several factors, including race, to fill the remaining spots. Upon a second review of the case by the Supreme Court, a 4-3 opinion led by Justice Anthony M. Kennedy ruled that the university’s policy met the standard of strict scrutiny, meaning this was okay for the school to do.

Affirmative Action in Colleges and Universities

If you’re like me, you’re reading through this timeline and thinking that a lot of these policies seem directly aimed at businesses, while there’s no clear law that might ask a college or university to do something specific in regards to affirmative action. Affirmative action in colleges and universities was not enacted through a specific federal law, but rather through a series of executive orders and court rulings. Executive Order 10925 in 1961 and Executive Order 11246 in 1965 are cited when discussing affrimative action in schooling. The Supreme Court case of Regents of the University of California v. Bakke in 1978 upheld the constitutionality of affirmative action in a university setting. Since then, there have been ongoing debates and legal challenges regarding the implementation of affirmative action in college admissions. The policies and specific requirements for affirmative action have varied across states and institutions, with some implementing more extensive programs than others. However, affirmative action as a concept has been recognized and practiced by many colleges and universities throughout the country. Personally, I’m always surprised by the ways laws work in the United States. From what we hear and see on the news, you would imagine schools were being forced to meet quotas (which is actually unconstitutional) or do something really specific and widespread, but thats completely not the case.

So, what positive impact has affirmative action had on colleges and universities?

Affirmative action has played a crucial role in fostering diversity on college campuses. By considering race or ethnicity as one factor among many in the admissions process, universities have been able to create more inclusive environments that reflect the broader society. It also seeks to address historical and ongoing inequalities by providing equal opportunities for underrepresented groups, such as Black Americans, Latinx Americans, and Indigenous peoples. It acknowledges that systemic barriers and discrimination have limited access to education for certain communities, and aims to level the playing field by considering the broader context in which applicants' achievements and qualifications are evaluated. Affirmative action has also helped mitigate the impact of unconscious biases that can influence the admissions process. Unconscious biases, often shaped by societal stereotypes, can unintentionally favor certain groups while disadvantaging others. By explicitly considering race or ethnicity, universities can counteract these biases and ensure fairer evaluations. Affirmative action also contributes to breaking down stereotypes and reducing isolation on college campuses. It helps create environments where students can engage with diverse peers, challenge stereotypes, and build relationships based on shared experiences and understanding. Affirmative action has been essential tool for advancing diversity and equal opportunity in higher education. Reports have shown that schools that once implemented affirmative action policies experience a massive drop in Black and Latinx students when those policies are changed. Without affirmative action, schools will surely become more white and less diverse.

The most noteworthy and compelling piece of the affirmative action conversation, in my opinion is the concept that affirmative action is an inherently unequal policy alongside the inescapable fact that historic inequalities exist in America. The truth is, there are so many ways in which everyday Americans are afforded certain privileges in education, business, housing, funding, and nearly every facet of life. It is noteworthy that affirmative action is often attacked when these other areas are not. The next newsletter will discuss some of these concepts along with more reactions to the most recent Supreme Court decision. See ya then.

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

Stop and Frisk

Stop and frisk was up for debate in the 1968 Terry v. Ohio supreme court case which found it to be legal, and set this precedent: “Under the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, a police officer may stop a suspect on the street and frisk him or her without probable cause to arrest…” Stop and frisk historically has targeted Black and Latinx New Yorkers, let’s talk about it.

Hi Friends!

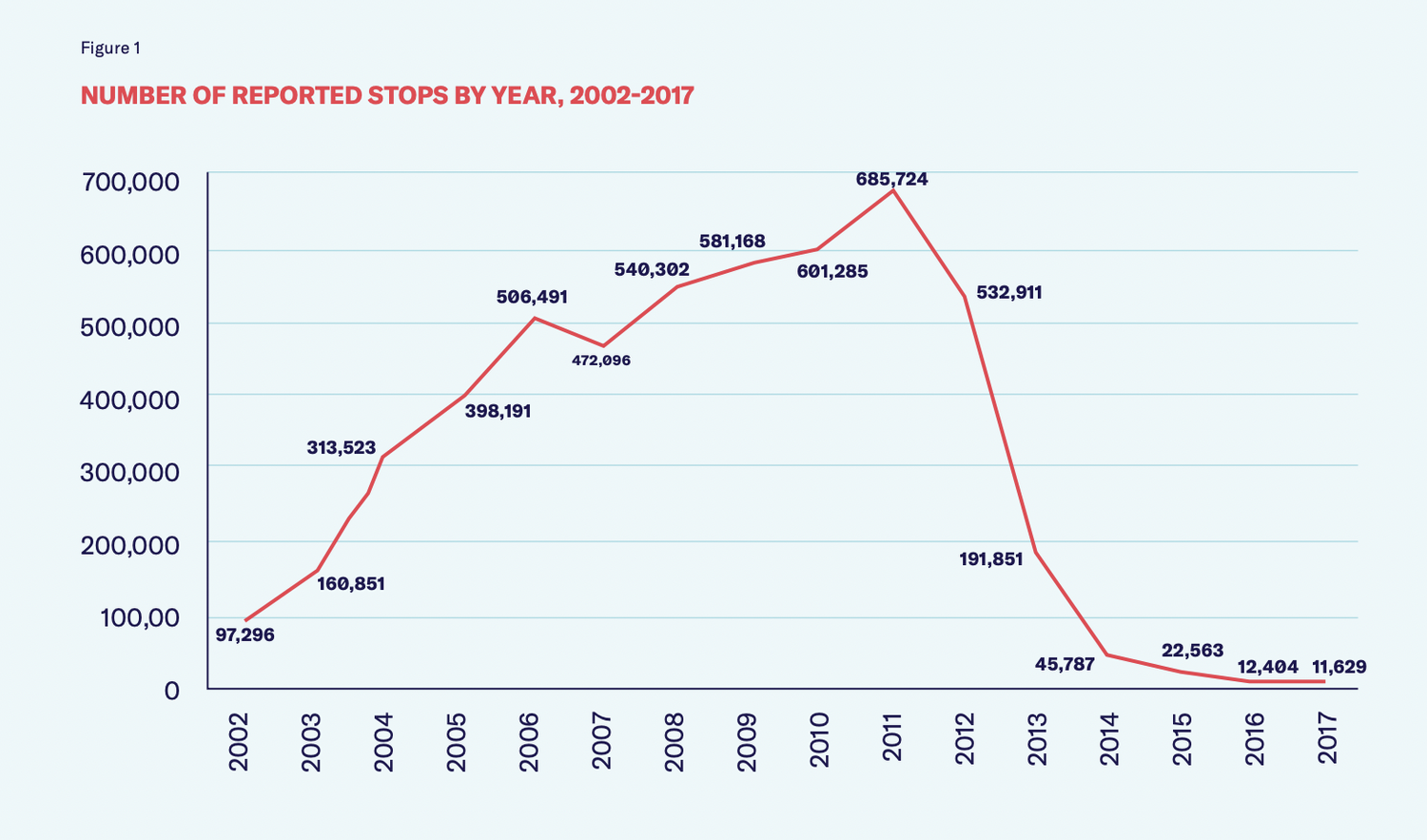

Welcome to Issue 53 of this newsletter. This week’s topic is: Stop and Frisk. I was inspired to write on this topic from some of my reading for a class I’m taking at Columbia called “Human Rights in the United States”. Stop and frisk was up for debate at the 1968 Terry v. Ohio supreme court case which found it to be legal, and set this precedent: “Under the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, a police officer may stop a suspect on the street and frisk him or her without probable cause to arrest, if the police officer has a reasonable suspicion that the person has committed, is committing, or is about to commit a crime and has a reasonable belief that the person ‘may be armed and presently dangerous.’" Outside of New York, this practice is known as a Terry Stop, based on the name of the case. However, in 2013, in Floyd v. City of New York, US District Court Judge Shira Scheindlin ruled that stop-and-frisk had been used in an unconstitutional manner due to racial profiling and directed the police to adopt a written policy to specify where such stops are authorized. Stop and frisk was a signature policy of the Bloomberg administration beginning in 2002 and reaching its peak in 2011 with over 600,000 incidents that year alone. A . According to a highly researched study by the NYCLU, “over 97 percent of all stops that occurred from 2003-2021 took place during [Bloomberg’s] time in office.” Stop and frisk never reduced crime, but always took a toll of Black and Latinx communities. Let’s get into it!

Key Terms

Stop and frisk: The controversial policy allowed police officers to stop, interrogate and search New York City citizens on the sole basis of “reasonable suspicion.”

Terry v. Ohio: A Cleveland detective (McFadden), on a downtown beat which he had been patrolling for many years, observed two strangers (petitioner and another man, Chilton) on a street corner. Suspecting the two men of "casing a job, a stick-up," the officer followed them and saw them rejoin the third man a couple of blocks away in front of a store. The officer approached the three, identified himself as a policeman, spun petitioner around, patted down his outside clothing, and found in his overcoat pocket, but was unable to remove, a pistol. . The court distinguished between an investigatory "stop" and an arrest, and between a "frisk" of the outer clothing for weapons and a full-blown search for evidence of crime. Under the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, a police officer may stop a suspect on the street and frisk him or her without probable cause to arrest, if the police officer has a reasonable suspicion that the person has committed, is committing, or is about to commit a crime and has a reasonable belief that the person "may be armed and presently dangerous."

Floyd v. City of New York: The Center for Constitutional Rights filed the federal class action lawsuit Floyd, et al. v. City of New York, et al. against the City of New York to challenge the New York Police Department’s practices of racial profiling and unconstitutional stop and frisks of New York City residents. The named plaintiffs in the case – David Floyd, David Ourlicht, Lalit Clarkson, and Deon Dennis – represent the thousands of primarily Black and Latino New Yorkers who have been stopped without any cause on the way to work or home from school, in front of their house, or just walking down the street. In a historic ruling on August 12, 2013, following a nine-week trial, a federal judge found the New York City Police Department liable for a pattern and practice of racial profiling and unconstitutional stops. Floyd focuses not only on the lack of any reasonable suspicion to make these stops, in violation of the Fourth Amendment, but also on the obvious racial disparities in who is stopped and searched by the NYPD.

Broken Windows Theory: Kelling and Wilson suggested that a broken window or other visible signs of disorder or decay — think loitering, graffiti, prostitution or drug use — can send the signal that a neighborhood is uncared for. So, they thought, if police departments addressed those problems, maybe the bigger crimes wouldn't happen. Stop and frisk was seen as a way of managing this. Kelling and Wilson proposed that police departments change their focus. Instead of channeling most resources into solving major crimes, they should instead try to clean up the streets and maintain order — such as keeping people from smoking pot in public and cracking down on subway fare beaters. If broken windows meant arresting people for misdemeanors in hopes of preventing more serious crimes, "stop and frisk" said, why even wait for the misdemeanor? Why not go ahead and stop, question and search anyone who looked suspicious? In Chicago, the researchers Robert Sampson and Stephen Raudenbush analyzed what makes people perceive social disorder. They found that if two neighborhoods had exactly the same amount of graffiti and litter and loitering, people saw more disorder, more broken windows, in neighborhoods with more African-Americans.

Let’s Get Into It

A 2019 report by NYCLU on Stop and Frisk encapsulated so much relevant information to how this system has operated in New York City, so all of the info below will be pulled from there.

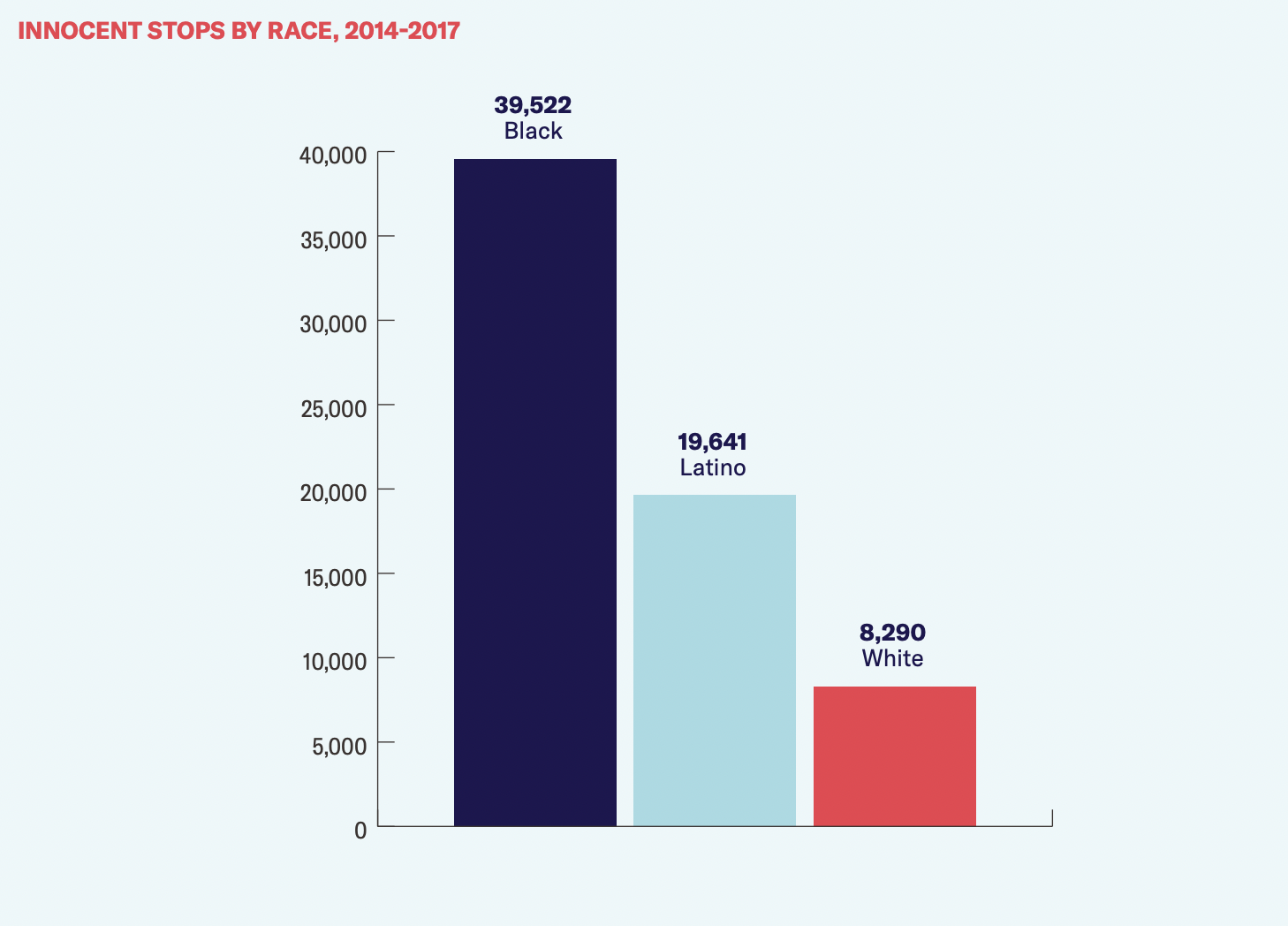

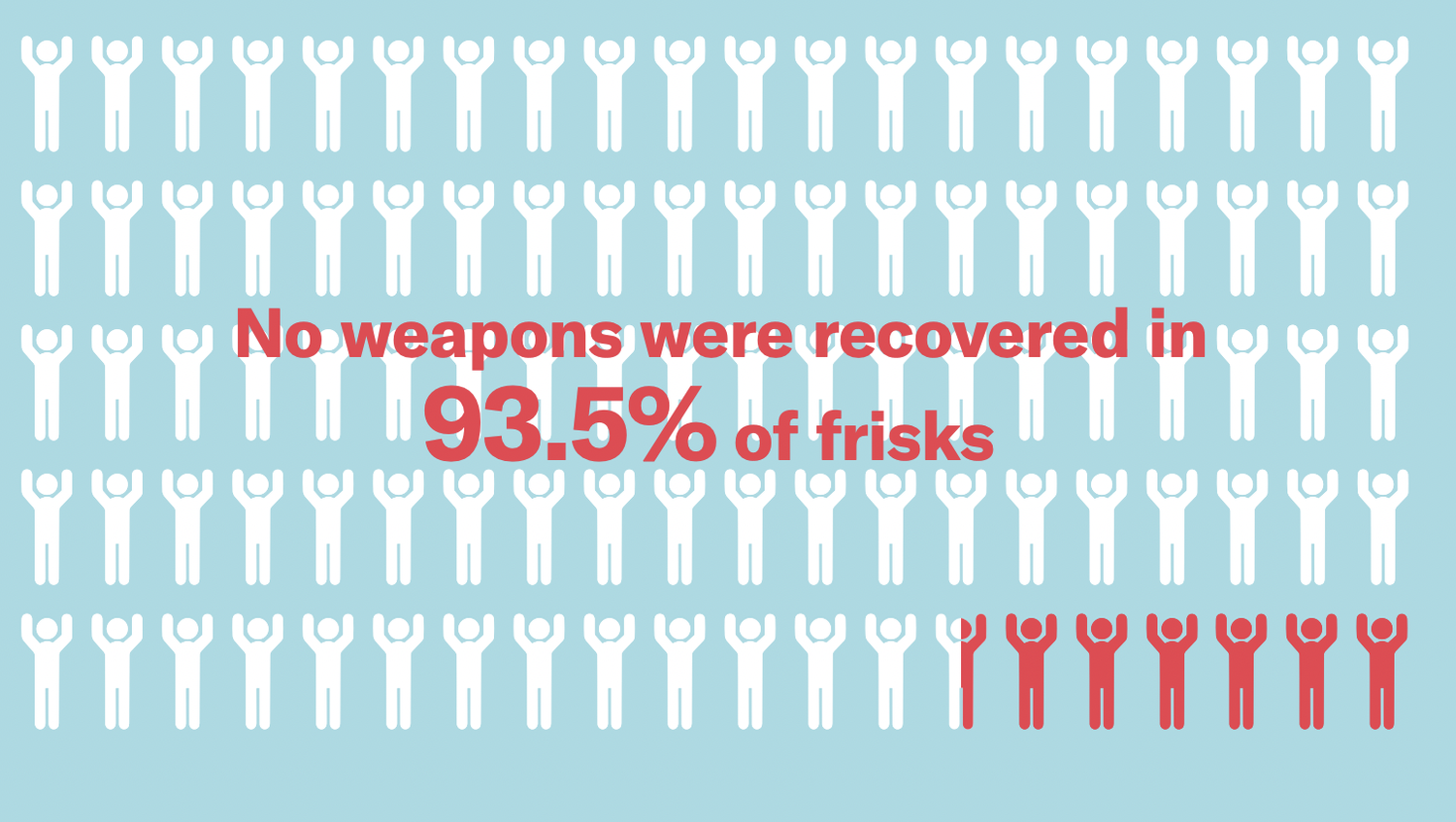

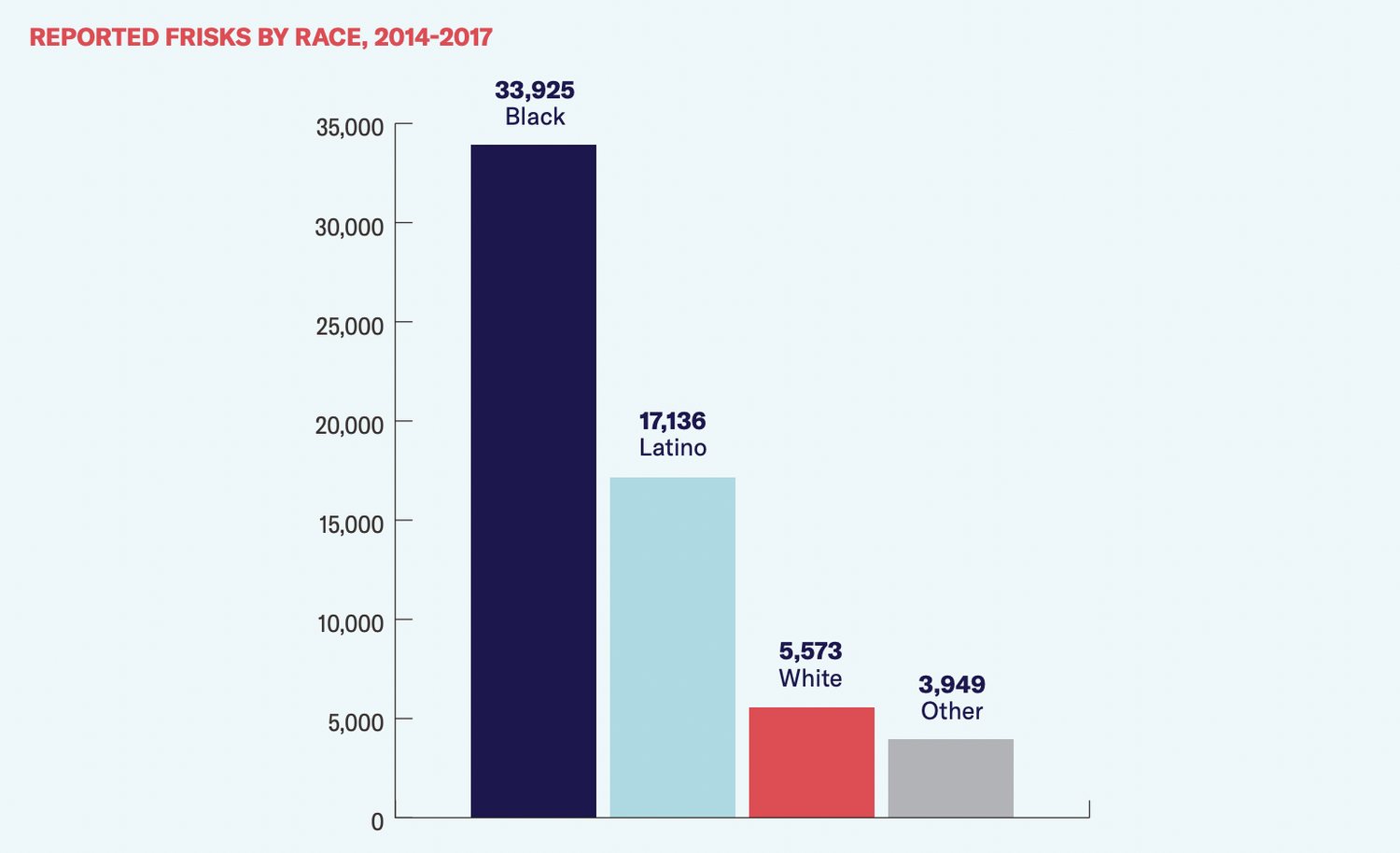

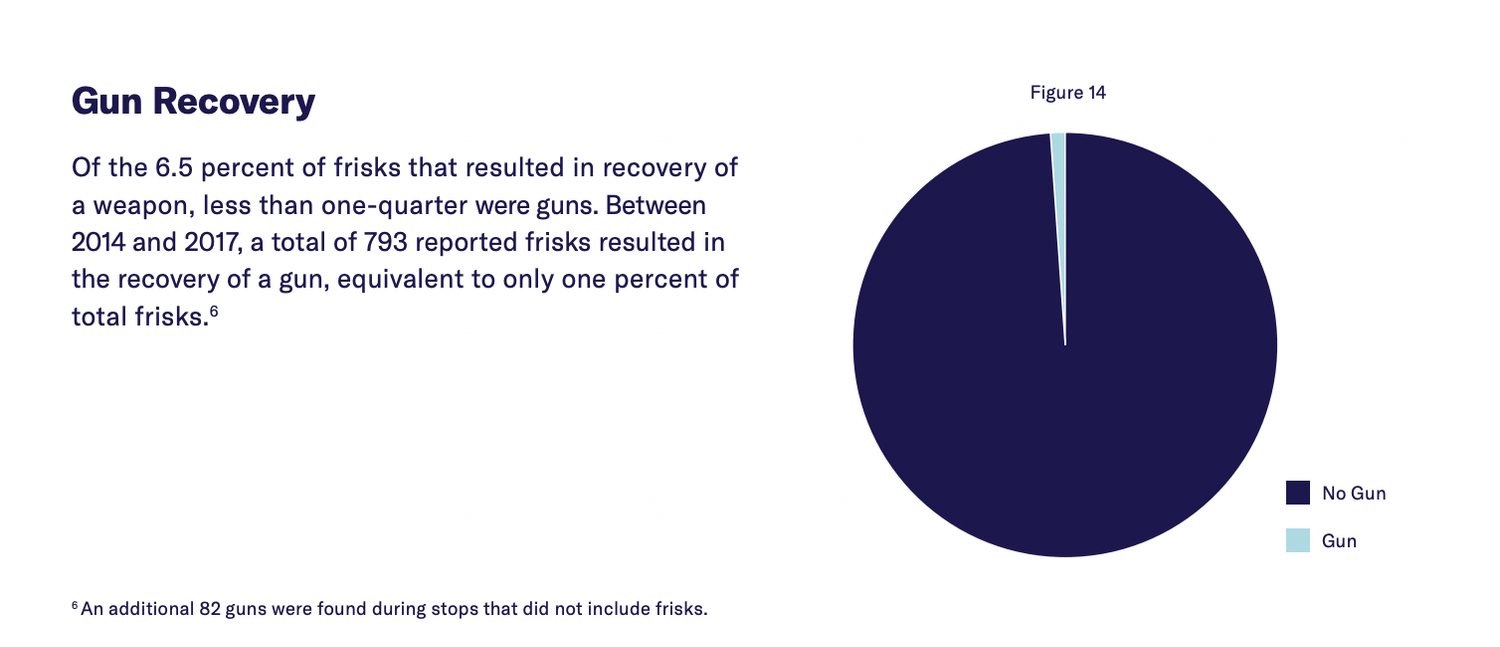

The New York City Police Department’s aggressive stop-and-frisk program exploded into a national controversy during the mayoral administration of Michael Bloomberg, as the number of NYPD stops each year grew to hundreds of thousands. Most of the people stopped were black and Latino, and nearly all were innocent. Stop-and-frisk peaked in 2011, when NYPD officers made nearly 700,000 stops.

It is notable that “actions of engaging in a violent crime” was a reason listed in only seven percent of reported stops between 2014 and 2016. During the height of stop-and-frisk, the NYPD routinely argued that the disproportionate number of stops of Black people was justified because, according to the department, Black people are disproportionately involved in violent crimes. Given that over 90 percent of stops had nothing to do with a suspected violent crime, the race of those convicted of violent crimes generally cannot explain the disproportionate number of Black people stopped every year

Stops of Males Age 14-24

24.9% (22,998) Young Black Males but only 1.9% (158,406) of NYC’s population

12.8% (11,193) Young Latino Males but only 2.8% (226,677) of NYC’s population

In 2011, 685,724 NYPD stops were recorded — this is at the peak of Stop and Frisk under Bloomberg

605,328 were innocent (88 percent).

350,743 were Black (53 percent).

223,740 were Latinx (34 percent).

61,805 were white (9 percent).

In 2021, 8,947 stops were recorded.

5,422 were innocent (61 percent).

5,404 were Black (60 percent).

2,457 were Latinx (27 percent).

732 were white (8 percent).

192 were Asian / Pacific Islander (2 percent)

71 were Middle Eastern/Southwest Asian (1 percent)

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

2019 Bail Reform Law

In short, this law virtually eliminated bail for the most common, non-violent crimes, and reduced our jail populations by over 30%. By April of 2020, however, due to fearmongering and unsubstantiated claims made by groups like the NYPD, 12 crimes had their new bail policies rolled back, rendering the original law virtually useless. Remember — bail criminalizes poverty.

Hello Friends!

Happy New Year and welcome back, this is Issue 52!

I’m so excited to share that I finished my first semester at Columbia with a 4.0! For my final paper, I wrote about the 2019 bail reform law in New York. In short, this law virtually eliminated bail for the most common, non-violent crimes, and reduced our jail populations by over 30%. By April of 2020, however, due to fearmongering and unsubstantiated claims made by groups like the NYPD, 12 crimes had their new bail policies rolled back, rendering the original law virtually useless.

Remember — bail criminalizes poverty.

This is how the jail system works: you are accused of a crime or potentially found in a position that seems suspicious, you’re taking to jail, you brought before a judge for arraignment, the judge decides if you are allowed to post bail before your trial or not and sets an amount, the bail is due immediately. If you are unable to pay bail, you stay in jail to await trial. (Jail is a temporary space for shorter sentences and those that cannot pay bail, prison is for longer sentences after your trial has occurred). Take note that you are in jail while you await trial, meaning, you are still not sentenced at this time. In Rikers Island, one of New York’s most notorious jails, only 10% are released within 24 hours, while 25% stay locked up awaiting trial for two months or longer. If these individuals could afford to pay bail, many would be home with their families, continuing to work and live their lives during these months.

Kalief Browder was held at Rikers for three years from 2010-2013, spending over two of those years in solitary confinement — after being accused of stealing a backpack, a crime which he plead “not-guilty” to. His trial was delayed by a backlog of work at the Bronx County District Attorney's office. Eventually the case was dismissed after Browder experienced irreparable mental, emotional and physical abuse. He eventually died by suicide in 2015 after suffering from his trauma. He said while being in jail “I feel like I was robbed of my happiness.”

The money-driven bail system in America is inhuman, unjust and blatantly criminalizes poverty — which is inextricably tied to race in America. If you want to learn more about the 2019 bail reform in New York through a human rights lens, check out my final paper below.

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

Cash Bail

When someone is accused of a crime, a judge decides if they are 1) held without bail, 2) released, 3) held with bail. If someone cannot pay bail, they go to jail. This is before they have a trial. Every day, nearly half a million individuals sit in local jails who have not been convicted of any crime. Why are most of them there? Because they cannot afford cash bail. To avoid this, many people plead guilty and take a plea deal instead of waiting for a trail. Only about 5% of cases go to trial at all. This has lasting consequences. Bail criminalizes poverty.

Hi Friends!

Welcome to Issue 51 newsletter. This week’s topic is: The Cash Bail System in America. First and foremost, we should establish what bail is and how it’s used. The terms “jail” and “prison” are often used interchangeably, but they actually are two separate institutions. A jail is for short-term sentences, or where someone waits for trial. A prison is for a long-term sentence, including a life sentence. There are other differences between jails and prisons in terms of who oversees them, what the incarcerated person can access, potential resources and more. In 2019, there were “1,566 state prisons, 102 federal prisons, 2,850 local jails, 1,510 juvenile correctional facilities, 186 immigration detention facilities, and 82 Indian country jails, as well as in military prisons, civil commitment centers, state psychiatric hospitals, and prisons in the U.S. territories.” When someone is accused of a crime, a judge decides if they are 1) held without bail, 2) released, 3) held with bail. If someone cannot pay bail, they go to jail. This is before they have a trial. Every day, nearly half a million individuals sit in local jails who have not been convicted of any crime. Why are most of them there? Because they cannot afford cash bail. In 2014, only 14% of New Yorkers could afford to pay their bail, meaning 86% of those accused of a crime were sitting in jails for days, weeks, or even years. To avoid this, many people plead guilty and take a plea deal instead of waiting for a trail. Only about 5% of cases go to trial at all. This has lasting consequences. Bail criminalizes poverty. Let’s get into it.

Key Terms

Bail: Cash bail is a refundable, court-determined fee that a defendant pays—regardless of guilt or innocence—to await trial at home instead of in jail. While “innocent until proven guilty” is ingrained in the American psyche, the use of bail means that if you can’t pay you serve jail time.

Bond: The words “bail” and “bond” are often used almost interchangeably when discussing jail release, and while they are closely related to each other, they are not the same thing. Bail is the money a defendant must pay in order to get out of jail. A bond is posted on a defendant’s behalf, usually by a bail bond company, to secure his or her release.

Bail Schedule: A bail schedule is a list of bail amount recommendations for different charges. Some states allow defendants to post bail with the police before they go to their first court appearance. The required amount of bail will depend on the crime that the defendant allegedly committed. A key difference between police bail schedules and bail determinations by judges is that a judge has discretion to alter the amount. They can consider many different factors, such as a defendant’s criminal history, employment status, and ties to the community. These intangible factors do not affect the bail schedule in a jail. If you are unwilling to pay the amount required by the bail schedule, you likely will need to go to court and present your case to a judge.

Plea Deal: Plea deals—which are entirely within the discretion of a prosecutor to offer (or accept)—typically include one or more of the following: 1) the dismissal of one or more charges, and/or agreement to a conviction to a lesser offense, 2) an agreement to a more lenient sentence and length, 3) an agreement to stipulate to a version of events that omits certain facts that would statutorily expose a person to harsher penalties.

Criminal Conviction: Besides direct consequences that can include jail time, fines, and treatment, a criminal conviction can trigger many consequences outside of the criminal court system. These consequences can affect your current job, future job opportunities, housing choices, immigration status. You may have to disclose your criminal record to employers. You may find it difficult to obtain a mortgage, auto loan, business loan, or other loan due to your criminal conviction. While a conviction does not automatically eliminate your eligibility for financial aid for college, it could impact on your ability to qualify. Landlords often conduct background checks before approving a prospective tenant and may not approve you for housing. In some states, you could lose your right to vote, serve on a jury, or hold a public office if you are convicted of a felony. Your conviction could have serious implications for your immigration status. Even a misdemeanor conviction can limit your ability to travel to other countries. You may lose custody of your children.

Risk Assessments: Developed and implemented by a mix of jurisdictions, states, private companies, nonprofit organizations and academic institutions, these special algorithms use factors such as age, education level, arrest record and home address to assign scores to defendants. Risk assessment tools are marketed as a way to automate a resource-strapped system and remove human bias. But critics say that they can amplify existing inequities, especially against young Black and Latino men and people experiencing mental illness. More than 60 percent of Americans live in a jurisdiction where the risk assessment tools are in use, according to Mapping Pretrial Injustice, a nonprofit data campaign critical of the tools.

The 8th Amendment: Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.

Let’s Get Into It

Fast Facts About Bail

COVID-19 has exacerbated bail issues and led to longer stays in jail for people who have yet to have a trial. In New York, for example, for people who do not make bail, average jail stays have become longer. The average number of days people were in custody in New York City jails rose from 198.4 in January 2020, or roughly six and a half months, to 286.5 days, or more than nine months, in August 2021 – a 44% increase.

The average length of pretrial incarceration in the US is 26 days

At any given time an estimated half a million Americans, or about two-thirds of the overall jail population, are incarcerated because they can’t afford their bail or a bond.

About 94% of felony convictions at the state level and about 97% at the federal level are the result of plea bargains. That means only 3%-6% of all cases actually go to trial.

Why Does Bail Exist And How Does It Work?

From The Marshall Project:

You’ve been arrested, taken to jail, fingerprinted and processed. Within 24 to 48 hours, you’ll go to an initial hearing known as an arraignment.

There, a judge will formally present the charges against you, and you will plead innocent or guilty. Then the judge either grants bail and sets the amount; releases you on your own recognizance without a fee; or denies you bail.

Bail is usually denied if a defendant is deemed a flight risk or a danger to the community because of the nature of the alleged crime.

If you get bail, you have three choices:

Pay the amount in full and get out of jail. You’ll get the money back when the trial is over, no matter the outcome.

Pay nothing. You’ll return to jail and await trial.

Secure a bail bond and get out of jail. In this case, you’ll pay a private agent known as a bondsman a portion of the amount, usually 10 percent and collateral such as a home or jewelry to cover the balance. (In turn, bail bond companies guarantee the full amount to the court.) The fee you pay for a bail bond is not refundable, even if your charges are dropped.

Resources

Friends, the bail system is absolutely horrific, and this is just scratching the surface.

I plan on discussing bail a lot more in this newsletter since it’s something I’m focusing a lot of thought on in school. This newsletter is just the start so I wanted to cover the basics. My final paper for one of my classes will center around bail, specifically as it impacts New Yorkers. Bail is absolutely heinous and destroys people’s lives. Let’s keep talking about it. See ya next week!

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

Human Rights

You probably know by now that I’m pursuing a masters degree from Columbia University in Human Rights Studies from the Institute for the Study of Human Rights. You might be wondering what that means. For a lot of us, we think of human rights as an umbrella term, a vague topic that covers a lot of different things. Racism, discrimination, homophobia, poverty, addiction, mental illness, refugee status — these might be some topics that pop into our heads when we think of human rights. But what exactly are capital H, capital R, Human Rights?

Hi Friends!

Welcome to Issue 50 of our newsletter. This week’s topic is: What Are Human Rights? You probably know by now that I’m pursuing a masters degree from Columbia University in Human Rights Studies from the Institute for the Study of Human Rights. You might be wondering what that means. For a lot of us, we think of human rights as an umbrella term, a vague topic that covers a lot of different things. Racism, discrimination, homophobia, poverty, addiction, mental illness, refugee status — these might be some topics that pop into our heads when we think of human rights. But what exactly are capital H, capital R, Human Rights? It’s actually a very specific area of study, let’s get into it!

Key Terms

Human Rights: Human rights are rights we have simply because we exist as human beings - they are not granted by any state. These universal rights are inherent to us all, regardless of nationality, sex, national or ethnic origin, color, religion, language, or any other status. They range from the most fundamental - the right to life - to those that make life worth living, such as the rights to food, education, work, health, and liberty.

Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR): Adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1948, was the first legal document to set out the fundamental human rights to be universally protected. The UDHR, which turned 74 in 2022, continues to be the foundation of all international human rights law. Its 30 articles provide the principles and building blocks of current and future human rights conventions, treaties and other legal instruments. The UDHR, together with the 2 covenants - the International Covenant for Civil and Political Rights, and the International Covenant for Economic, Social and Cultural Rights - make up the International Bill of Rights.

Respect, Protect and Fulfill: All countries in the world should seek to respect, protect and fulfill the rights of its citizens. The obligation to respect means that States must refrain from interfering with or curtailing the enjoyment of human rights. The obligation to protect requires States to protect individuals and groups against human rights abuses. The obligation to fulfill means that States must take positive action to facilitate the enjoyment of basic human rights.

United Nations: The United Nations is an international organization founded in 1945. Currently made up of 193 Member States, the UN and its work are guided by the purposes and principles contained in its founding Charter. The UN has evolved over the years to keep pace with a rapidly changing world.

Let’s Get Into It

Universal Declaration Of Human Rights (UDHR)

The UDHR codified the meaning of human rights. It’s comprised of 30 articles and these articles tell the world — these are your rights, no one has to give them to you, you get them just for being a human being, and when we talk about Human Rights, these are the exact things we are talking about! Some of the most important rights included in this document are:

Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.

Article 2: Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, etc.

Article 3: Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security.

Article 4: No one shall be held in slavery or servitude.

Article 4: No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

Article 7: All are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimination to equal protection of the law.

Article 11: Everyone charged with a penal offence has the right to be presumed innocent until proved guilty.

Article 13: Everyone has the right to freedom of movement and residence within the borders of each state. Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country.

Article 16: Men and women of full age, without any limitation due to race, nationality or religion, have the right to marry and to found a family.

Article 18: Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion.

Article 19: Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression.

Article 23: Everyone, without any discrimination, has the right to equal pay for equal work.

Article 24: Everyone has the right to rest and leisure, including reasonable limitation of working hours and periodic holidays with pay.

Article 25: Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family.

Article 26: Everyone has the right to education.

Now, if you’re anything like me, you read this and feel a little confused. How can the whole world be entitled to these things? How can the intent of this document be to impact every human being, when so many are clearly, openly and actively being denied these human rights? I am especially struck by Article 4 and it’s direct contradiction to the United States prison system. I am struck by Article 24 and the ways in which so many Americans live paycheck to paycheck without any sort of safetynet or compassion, without any true access to rest or leisure and absolutely without “reasonable limitation of working hours.” Let’s continue to discuss the ways in which America falls short when discussing Human Rights.

Human Rights In The United States

The United Nations’ Universal Human Rights Index is “a repository of recommendations and observations issued by bodies of the United Nations human rights monitoring system” — meaning, various countries will share recommendations for one another and this is where all of those recommendations are logged. When we look at the United States, we see the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination has made the most recommendations, with 187 recommendations listed. There are even recommendations around these topics under the general Human Rights Committee, with 105 recommendations, many including discrimination and concerns around the prison system. This is no surprise. The rest of the world looks at the United States and sees racism and discrimination as one of — if not THE — key concern. According to Pew Research: “Between 82% and 95% in every public outside of the U.S. believe this kind of discrimination is at least a somewhat serious problem, and more than four-in-ten call it very serious..”

Other top concerns in the United States around human rights violations are: child prostitution, the carceral system, gender discrimination, adequate housing as a component of the right to an adequate standard of living, the human rights of migrant and safe drinking water.

While there is so much more to share around Human Rights and the issues that impact the lives of Americans, I felt like this was a helpful introduction. Something I took away from some of my early discussions at school is that the UDHR clearly spells out what the basis for human rights violations are. In this way, while some things might feel bad, they may not truly be a violation of our human rights. Crimes and human rights violations can intersect, but they can also be different. As I continue to learn more about human rights through my school and eventual research and thesis, I’ll be sure to bring you along. See ya next time!

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

War On Drugs

The War on Drugs is a phrase used to refer to a government-led initiative that aims to stop illegal drug use, distribution and trade by dramatically increasing prison sentences for both drug dealers and users. This drug war has led to unintended consequences that have proliferated violence around the world and contributed to mass incarceration in the US.

Hi Friends!

Welcome to Issue 49 of this newsletter. This week’s topic is The War On Drugs. “The War on Drugs is a phrase used to refer to a government-led initiative that aims to stop illegal drug use, distribution and trade by dramatically increasing prison sentences for both drug dealers and users. The movement started in the 1970s and is still evolving today.” The War on Drugs was popularized by Richard Nixon who said, "If we cannot destroy the drug menace in America, then it will surely in time destroy us," Nixon told Congress in 1971. "I am not prepared to accept this alternative." This drug war has led to consequences that have proliferated violence around the world and contributed to mass incarceration in the US. Let’s get into it!

Key Terms

The War On Drugs: The War on Drugs is a phrase used to refer to a government-led initiative that aims to stop illegal drug use, distribution and trade by dramatically increasing prison sentences for both drug dealers and users. The movement started in the 1970s and is still evolving today.

The Drug Scheduling System: Under the Controlled Substances Act, the federal government — which has largely relegated the regulation of drugs to the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) — puts each drug into a classification, known as a schedule, based on its medical value and potential for abuse. You can view the current Drug Schedules here.

Let’s Get Into It

Drug Use In America Before The “War On Drugs”

According to historian Peter Knight, opium largely came over to America with Chinese immigrants on the West Coast. Americans, already skeptical of the drug, quickly latched on to xenophobic beliefs that opium somehow made Chinese immigrants dangerous.

Cocaine was similarly attached in fear to Black communities, neuroscientist Carl Hart wrote for the Nation. The belief was so widespread that the New York Times even felt comfortable writing headlines in 1914 that claimed "Negro cocaine 'fiends' are a new southern menace."

Drug use for medicinal and recreational purposes has been happening in the United States since the country’s inception. In the 1890s, the popular Sears and Roebuck catalogue included an offer for a syringe and small amount of cocaine for $1.50.

In some states, laws to ban or regulate drugs were passed in the 1800s, and the first congressional act to levy taxes on morphine and opium took place in 1890.

The Smoking Opium Exclusion Act in 1909 banned the possession, importation and use of opium for smoking.

In 1914, Congress passed the Harrison Act, which regulated and taxed the production, importation, and distribution of opiates and cocaine.

In 1919, the 18th Amendment was ratified, banning the manufacture, transportation or sale of intoxicating liquors, ushering in the Prohibition Era. The same year, Congress passed the National Prohibition Act (also known as the Volstead Act), which provided guidelines on how to federally enforce Prohibition.

In 1937, the “Marihuana Tax Act” was passed. This federal law placed a tax on the sale of cannabis, hemp, or marijuana. While the law didn’t criminalize the possession or use of marijuana, it included hefty penalties if taxes weren’t paid, including a fine of up to $2000 and five years in prison.

The War On Drugs

President Richard M. Nixon signed the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) into law in 1970.

In June 1971, Nixon officially declared a “War on Drugs,” stating that drug abuse was “public enemy number one.”

Nixon went on to create the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) in 1973.

In the mid-1970s, the War on Drugs took a slight hiatus. Between 1973 and 1977, eleven states decriminalized marijuana possession.

Jimmy Carter became president in 1977 after running on a political campaign to decriminalize marijuana.

In the 1980s, President Ronald Reagan reinforced and expanded many of Nixon’s War on Drugs policies. In 1984, his wife Nancy Reagan launched the “Just Say No” campaign, which was intended to highlight the dangers of drug use.

In 1986, Congress passed the Anti-Drug Abuse Act, which established mandatory minimum prison sentences for certain drug offenses.

On September 5, 1989, in his first televised national address as president, George H.W. Bush called drugs "the greatest domestic threat facing our nation today," held up a bag of seized crack cocaine, and vowed to escalate funding for the war on drugs. He later approved, among other drug-related policies, the 1033 program (then known as the 1208 program) that equipped local and state police with military-grade equipment for anti-drug operations.

It’s Impact On Incarceration And Racist History

The escalation of the criminal justice system's reach over the past few decades, ranging from more incarceration to seizures of private property and militarization, can be traced back to the war on drugs. After the US stepped up the drug war throughout the 1970s and '80s, harsher sentences for drug offenses played a role in turning the country into the world's leader in incarceration.

During a 1994 interview, President Nixon’s domestic policy chief, John Ehrlichman, provided inside information suggesting that the War on Drugs campaign had ulterior motives, he was quoted saying:

“We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course, we did.”

When the 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act was passed, it was heavily criticized as having racist ramifications because it allocated longer prison sentences for offenses involving the same amount of crack cocaine (used more often by Black Americans) as powder cocaine (used more often by white Americans). 5 grams of crack triggered an automatic 5 year sentence, while it took 500 grams of powder cocaine to merit the same sentence.

Critics pointed to data showing that people of color were targeted and arrested on suspicion of drug use at higher rates than whites.

Overall, the policies led to a rapid rise in incarcerations for nonviolent drug offenses, from 50,000 in 1980 to 400,000 in 1997. In 2014, nearly half of the 186,000 people serving time in federal prisons in the United States had been incarcerated on drug-related charges, according to the Federal Bureau of Prisons.

The number of Black men in prison (792,000) has already equaled the number of men enslaved in 1820. With the current momentum of the drug war fueling an ever expanding prison-industrial complex, if current trends continue, only 15 years remain before the United States incarcerates as many African-American men as were forced into chattel bondage at slavery's peak, in 1860.

The War On Drugs Today

Today, the US still continues to have the largest prison population on the planet. Learn more about it in my newsletters on Prison Reform.

Between 2009 and 2013, some 40 states took steps to soften their drug laws, lowering penalties and shortening mandatory minimum sentences, according to the Pew Research Center.

In 2010, Congress passed the Fair Sentencing Act (FSA), which reduced the discrepancy between crack and powder cocaine offenses from 100:1 to 18:1.

The recent legalization of marijuana in several states and the District of Columbia has also led to a more tolerant political view on recreational drug use. However, estimated 40,000 people today are incarcerated for marijuana offenses even as the overall legal cannabis industry is booming; one state after another is legalizing; and cannabis companies are making healthy profits.

Although Black communities aren't more likely to use or sell drugs, they are much more likely to be arrested and incarcerated for drug offenses.

A 2014 study from Peter Reuter at the University of Maryland and Harold Pollack at the University of Chicago found there's no good evidence that tougher punishments or harsher supply-elimination efforts do a better job of pushing down access to drugs and substance abuse than lighter penalties.

Most of the reduction in accessibility from the drug war appears to be a result of the simple fact that drugs are illegal, which by itself makes drugs more expensive and less accessible by eliminating avenues toward mass production and distribution.

Enforcing the war on drugs costs the US more than $51 billion each year, according to the Drug Policy Alliance. As of 2012, the US had spent $1 trillion on anti-drug efforts.

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

Bystander Intervention

An engaged bystander is someone who lives up to that responsibility by intervening before, during, or after a situation when they see or hear behaviors that threaten, harass, or otherwise encourage violence. Bystander Intervention is a social science model that predicts the likelihood of individuals (or groups) willing to actively address a situation they deem problematic.

Hi Friends!

Welcome to Issue 49 of this newsletter. This week’s topic is Bystander Intervention. An engaged bystander is someone who lives up to that responsibility by intervening before, during, or after a situation when they see or hear behaviors that threaten, harass, or otherwise encourage violence. Bystander Intervention is a social science model that predicts the likelihood of individuals (or groups) willing to actively address a situation they deem problematic. I remember my parents telling me about the Kitty Genovese Case, where a woman was attacked and killed on the street in Queens and 37 people saw it happen, but no one helped her. As a child, my parents always encouraged me to step up and say something. I live my life operating from a place of, “If I don’t say something, who will?” Bystander Intervention does not mean jeopardizing your wellbeing or confronting violence with violence. Let’s get into it!

Key Terms

Bystander: A bystander is anyone who observes a situation. We all observe numerous incidents and interactions daily, but usually do not acknowledge the situation as needing our response. An active bystander is someone who acknowledges a problematic situation and chooses how to respond.

Bystander Intervention: Bystander Intervention is a social science model that predicts the likelihood of individuals (or groups) willing to actively address a situation they deem problematic.

The Bystander Effect: The Bystander effect is a phenomenon in which people are less likely to help someone in an emergency due to the presence of the people (bystanders) around them. The phenomenon of the bystander effect was first explained by two psychologists named John Darley and Bibb Latané in 1968. Darley and Latané proposed that with the increase in the number of people around the person in the emergency, the people become less likely to help the one in need.

The Virtual Bystander Effect: With the rise in the impact of social media on people’s lives, the influence of the bystander effect has also evolved on the digital platform. The social media platforms allow us to get aware of the injustice happening in the nearby or the faraway places. The impact of the bystander effect on social platforms is even more than the real world as one can not see that how other people are physically reacting to the given situation. Examples include the 2017 sexual assault of a teenage girl by a group of five men was Live broadcast on Facebook and a Facebook Live broadcast of a man with a mental disability being tortured by a group of people. In both cases no one alerted the authorities.

Let’s Get Into It

Before diving into how to be a better bystander and what steps to take to safely intervene, we first must understand the Bystander Effect and the overall concept that—odds are— you probably won’t help someone in need if you think it’s someone else’s responsibility to do so. While it’s not always safe to personally intervene, it’s always possible to alert the proper authorities, take to social media to amplify a message, or seek help in some other manner.

The Bystander Effect

The Bystander Effect does not only affect everyday people. One example is an incident of a 53-year-old resident of Alameda, California named Raymond Zack. Raymond went into the water and when his foster mother called authorities, alerting them that Raymond might be trying to harm himself, both police and fire fighters stood on the beach and did nothing. The police thought the fire department would act. The fire department thought the police would act. After hours, a random civilian went into the water and dragged Raymond out.

There are various factors that are responsible for the bystander effect:

Diffusion of Responsibility: Diffusion of responsibility occurs when a duty or task is shared between a group of people instead of only one person. The moral obligation to help does not fall only on one person, but the whole group that is witnessing the emergency. The blame for not helping can be shared instead of resting on only one person. The belief that another bystander in the group will offer help means you may not feel you have to engage.

Evaluation Apprehension: This refers to the fear of being judged by others when acting publicly. Individuals may feel afraid of being superseded by a superior helper, offering unwanted assistance, or facing the legal consequences of offering inferior and possibly dangerous assistance.

Pluralistic Ignorance: Due to pluralistic ignorance, people are less likely to help others as almost every person is looking for the other person to act first. Pluralistic ignorance basically means when you look around and see no one else is intervening, you think, “Hmm, I must be wrong to think this is an emergency or I must be getting the wrong social cues here because if no one else is reacting then I too should not react.”

Confusion of Responsibility: This occurs when a bystander fears that helping could lead others’ to believing that they are the perpetrator. This fear can cause people to not act in dire situations.

Latané and Darley (1970) proposed a five-step decision model of helping, during each of which bystanders can decide to do nothing:

Notice the event (or in a hurry and not notice).

Interpret the situation as an emergency (or assume that as others are not acting, it is not an emergency).

Assume responsibility (or assume that others will do this).

Know what to do (or not have the skills necessary to help).

Decide to help (or worry about danger, legislation, embarrassment, etc.).

Real Life Examples Of The Bystander Effect

Honestly, these examples were deeply disturbing. These examples are extremely useful because we like to think, “I would never do that, I would definitely step up and say something” — but studies show, the larger the group, the slower you will be to respond and the less responsible you will feel to act. These examples deal with everything from sexual assault to murder and how these victims were attacked with many bystanders around including teachers, principles, law enforcement, friends and classmates, without receiving any help.

How To Safely Intervene

When I was a little kid my mom would tell me over and over that if I was in danger I needed to drop all of my belongings (my backpack, my books, my toys) and run for safety. Practicing this prepared me to understand that if I was being chased or abducted or trying to flee an unsafe environment, the weight of my heavy backpack might slow me down. In the same way, we must prime ourselves to understand that if we see someone in danger, we are expectant and prepared to take action.

Before stepping in, try the ABC approach:

Assess for safety: If you see someone in trouble, ask yourself if you can help safely in any way. Remember, your personal safety is a priority – never put yourself at risk.

Be in a group: It’s safer to call out behaviour or intervene in a group. If this is not an option, report it to others who can act.

Care for the victim:Talk to the person who you think may need help. Ask them if they are OK.

When it comes to intervening safely, remember the four Ds – direct, distract, delegate, delay. These don’t have to be done in any specific order so consider what might be best in the situation!

Watch this three minute video on the four Ds

Direct action: This is the most direct and risky interaction. Call out negative behaviour, tell the person to stop or ask the victim if they are OK. Do this as a group if you can. Be polite. Don’t aggravate the situation - remain calm and state why something has offended you. Stick to exactly what has happened, don’t exaggerate.

Distract: Interrupt, start a conversation with the perpetrator to allow their potential target to move away or have friends intervene. Or come up with an idea to get the victim out of the situation – tell them they need to take a call, or you need to speak to them; any excuse to get them away to safety. Alternatively, try distracting, or redirecting the situation.

Delegate: If you are too embarrassed or shy to speak out, or you don’t feel safe to do so, get someone else to step in. Any decent venue has a zero tolerance policy on harassment, so the staff there will act. Remember, calling the authorities might not be the best option. Marginalized communities like communities of color and trans communities might not feel safer with law enforcement present.

Delay: If the situation is too dangerous to challenge then and there (such as there is the threat of violence or you are outnumbered) just walk away. Wait for the situation to pass then ask the victim later if they are OK. Or report it when it’s safe to do so – it’s never too late to act.

Intervening in a potential life or death situation can be terrifying. It can also be disturbingly calm, imagining nothing is wrong because everyone else is acting like nothing is wrong. Prepare yourself mentally and emotionally to intervene in a way that is safe, non violent, and thoughtful. Don’t follow the crowd. Be the one that wakes up the group and urges them that there is danger. As always, live life with purpose. “We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek.” See ya next time!

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

Reperations

The case for reparations is complex, but one of the main focuses is the reality that while white Americans had the opportunity to build wealth Black Americans (and many other marginalized groups) were not afforded the same opportunities to build generational wealth, security and societal advancement.

Hi Friends!

Welcome to Issue 47 of this newsletter. This week’s topic is Reparations. The word “reparations” out of context simply means “the making of amends for a wrong one has done, by paying money to or otherwise helping those who have been wronged.” In the context of American slavery, most people hear the word “reparations” and understand it to be a reference to all of the free labor enslaved people endured (not to mention the emotional, physical and mental trauma and abuse). You’ve probably heard “40 acres and a mule” referred to in your history class as a promise to former slaves, but do you know how that really went down? “Making the American Dream an equitable reality demands the same U.S. government that denied wealth to Blacks restore that deferred wealth through reparations to their descendants in the form of individual cash payments in the amount that will close the Black-white racial wealth divide.” Let’s get into it!

Key Terms

Jim Crow: Jim Crow was the name of the racial caste system which operated primarily, but not exclusively in southern and border states, between 1877 and the mid-1960s. Under Jim Crow, African Americans were relegated to the status of second class citizens.

Reparations: A system of redress for egregious injustices.

40 Acres and a Mule: After the Civil War, Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman issued Field Order, No. 15, confiscating Confederate land along the rice coast. Sherman would later order “40 acres and a mule” to thousands of Black families, which historians would later refer to as the first act of reparations to enslaved Black people. After Lincoln’s assassination on April 14, 1865, the order would be reversed and the land given to Black families would be rescinded and returned to White Confederate landowners.

The Marshall Plan: The Marshall Plan, also known as the European Recovery Program, was a U.S. program providing aid to Western Europe following the devastation of World War II. It was enacted in 1948 and provided more than $15 billion to help finance rebuilding efforts on the continent.

Field Order 15: On January 16, 1865, during the Civil War (1861-65), Union Gen. William T. Sherman issued his Special Field Order No. 15, which confiscated as Union property a strip of coastline stretching from Charleston, South Carolina, to the St. John’s River in Florida, including Georgia’s Sea Islands and the mainland thirty miles in from the coast. The order redistributed the roughly 400,000 acres of land to newly freed Black families in forty-acre segments. Additionally, some families were to receive mules left over from the war, hence 40 acres and a mule.

Let’s Get Into It

The case for reparations is complex, but one of the main focuses is the reality that while white Americans had the opportunity to build wealth Black Americans (and many other marginalized groups) were not afforded the same opportunities to build generational wealth, security and societal advancement. Read my newsletter on redlining for more on this as well.

In this article from Brookings, Rashawn Ray and Andre M. Perry share some important stats:

Today, the average white family has roughly 10 times the amount of wealth as the average Black family.

White college graduates have over seven times more wealth than Black college graduates.

In 1860, over $3 billion was the value assigned to the physical bodies of enslaved Black Americans to be used as free labor and production.

In 1861, the value placed on cotton produced by enslaved Blacks was $250 million.

Economists William “Sandy” Darity and Darrick Hamilton point out in their 2018 report, What We Get Wrong About Closing the Wealth Gap, “Blacks cannot close the racial wealth gap by changing their individual behavior –i.e. by assuming more ‘personal responsibility’ or acquiring the portfolio management insights associated with ‘[financial] literacy.’” In fact, white high school dropouts have more wealth than Black college graduates.

The racial wealth gap did not result from a lack of labor, it came from a lack of financial capital.

In 2016, white families had the highest median family wealth at $171,000, compared to Black and Hispanic families, which had $17,600 and $20,700, respectively

The United States has yet to compensate descendants of enslaved Black Americans for their labor. Nor has the federal government atoned for the lost equity from anti-Black housing, transportation, and business policy. Not only do racial wealth disparities reveal fallacies in the American Dream, the financial and social consequences are significant and wide-ranging. Wealth is positively correlated with better health, educational, and economic outcomes.