Weekly Anti-racism NewsletteR

Because it ain’t a trend, honey.

-

Taylor started her newsletter in 2020 and has been the sole author of almost one hundred blog mosts and almost two hundred weekly emails. A lifelong lover of learning, Taylor began researching topics of interest around anti-racism education and in a personal effort to learn more about all marginalized groups. When friends asked her to share her learnings, she started sending brief email synopsises with links to her favorite resources or summarizing her thoughts on social media. As the demand grew, she made a formal platform to gather all of her thoughts and share them with her community. After accumulating thousands of subscribers and writing across almost one hundred topics, Taylor pivoted from weekly newsletters to starting a podcast entitled On the Outside. Follow along with the podcast to learn more.

-

This newsletter covers topics from prison reform to colorism to supporting the LGBTQ+ community. Originally, this was solely a newsletter focused on anti-racism education, but soon, Taylor felt profoundly obligated to learn and share about all marginalized communities. Taylor seeks guidance from those personally affected by many of the topics she writes about, while always acknowledging the ways in which her own privilege shows up.

Biracial & Multiracial Identities in America

In October 2013 I distinctly remember seeing the Nation Geographics cover image below with the words “The Changing Face of America.” In this issue, these faces are described as “disrupting our expectations” as we see hair that doesn’t align with our expectations on eye color or skin tone that seems mismatched with a certain shaped nose. The bottom line is race is a social construct, it means nothing, but it means everything. It makes less and less sense as time passes and society becomes more integrated and cross culturalization becomes more common, yet we are still ruled by white supremacy.

Hi Friends!

Welcome to Issue 37 of this newsletter! This week’s topic is Biracial & Multiracial Identities in America. In the past, I’ve referred to myself as “mixed-race” because I am Latinx and Black, but really, that doesn’t mean I’m mixed-raced at all. The first step in having conversations around race and oppression is understanding the language that we use, and I was mistaken when I interpreted my intersectional identity as a mixed-race identity. In short, Latinx or Hispanic is not a race, it’s an ethnicity. And race—while tied to ethnicity—is based more on phenotype (or your appearance) than anything else. Some might say language makes these conversations too difficult, but I say it makes it more specific, more nuanced, and more interesting. This week we talk about the complexities in identities that are biracial or multiracial from the way they are interpreted in the US Census to the way they are experienced. Let’s get into it.

Key Terms

Race: Many constructions of race are associated with phenotypic traits and geographic ancestry. The concept of "race" as a classification system of humans based on visible physical characteristics emerged over the last five centuries, influenced by European colonialism. The concept has manifested in different forms based on social conditions of a particular group, often used to justify unequal treatment. These false notions of racial difference have become embedded in the beliefs and behaviours of society, especially in Western nations. Race is strongly linked to skin colour.

Ethnicity: A social construct that divides people into smaller social groups based on characteristics such as shared sense of group membership, values, behavioral patterns, language, political and economic interests, history and ancestral geographical base. It is usually an inherited status based on the society in which one lives. Membership of an ethnic group tends to be defined by a shared cultural heritage, ancestry, origin myth, history, homeland, language or dialect, symbolic systems such as religion, mythology and ritual, cuisine, dressing style, art or physical appearance. By way of language shift, acculturation, adoption and religious conversion, it is sometimes possible for individuals or groups to leave one ethnic group and become part of another. The social construct that ethnic groups share a similar gene pool has been contradicted within the scientific community as evidenced by data finding more genetic variation within ethnic groups compared to between ethnic groups. The only classifications for ethnicity on the US census is “Hispanic” or “Non-Hispanic”.

Nationality: A legal identification of a person in international law, establishing the person as a subject, a national, of a sovereign state. It affords the state jurisdiction over the person and affords the person the protection of the state against other states.

Multiracial: Having two or more races.

Monoracial: Having one race.

Intersectionality: Intersectionality is a framework for conceptualizing a person, group of people, or social problem as affected by a number of discriminations and disadvantages. It takes into account people’s overlapping identities and experiences in order to understand the complexity of prejudices they face.

American Indian or Alaska Native: A person having origins in any of the original peoples of North and South America (including Central America), and who maintains tribal affiliation or community attachment.

Asian: A person having origins in any of the original peoples of the Far East, Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent including, for example, Cambodia, China, India, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Pakistan, the Philippine Islands, Thailand, and Vietnam.

Black or African American: A person having origins in any of the black racial groups of Africa.

Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander: A person having origins in any of the original peoples of Hawaii, Guam, Samoa, or other Pacific Islands.

White: A person having origins in any of the original peoples of Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa.

Minority: Sociologist Louis Wirth (1945) defined a minority group as “any group of people who, because of their physical or cultural characteristics, are singled out from the others in the society in which they live for differential and unequal treatment, and who therefore regard themselves as objects of collective discrimination.” Note that being a numerical minority is not a characteristic of being a minority group; sometimes larger groups can be considered minority groups due to their lack of power. It is the lack of power that is the predominant characteristic of a minority, or subordinate group. For example, consider apartheid in South Africa, in which a numerical majority (the black inhabitants of the country) were exploited and oppressed by the white minority.

Person of Color: A person whose skin pigmentation is other than and especially darker than what is considered characteristic of people typically defined as white. A person who is of a race other than white or who is of mixed race

Marginalized: Marginalization is the act of relegating someone to an unimportant or powerless position, oppressing a person or a group, relegating them to the fringes of society.

Let’s Get Into It

From National Geographic's "The Changing Face of America"

In October 2013 I distinctly remember seeing the Nation Geographics cover image below with the words “The Changing Face of America.” In this issue, these faces are described as “disrupting our expectations” as we see hair that doesn’t align with our expectations on eye color or skin tone that seems mismatched with a certain shaped nose. This made a lasting impression on me because much like the faces in the photos I constantly have had my features questioned and scrutinized throughout my life. The bottom line is race is a social construct, it means nothing, but it means everything. It makes less and less sense as time passes and society becomes more integrated and cross culturalization becomes more common, yet we are still ruled by white supremacy. It’s a lot.

The US Census & Race

From National Geographic's "The Changing Face of America"

In 2015, Time Magazine wrote, “Half of all children in the U.S. will be nonwhite by 2020… and more than half the entire population by 2044.” Today, the US Census says America is 76% “White, alone” and 2.8% “Two or more races”. Getting accurate data when it comes to how Americans identify their race is tricky and often skewed. Let me share a little history to explain why.

Did you ever wonder why “Hispanic” was the only ethnicity on any census or on official US forms? In the 1930’s “Mexican” was listed as a race on the US Census while Mexican-Americans were often targeted and discriminated against, and Mexican-Americans didn’t want to check this box. Mexican-Americans and other Latinx groups like Puerto Ricans used their proximity to whiteness to challenge discrimination, claiming they too were fair enough to be considered “white” (remember race is mostly about how you look). In 1980, we see “Hispanic” pop up on the official US Census after various attempts at collecting this data. They asked people to categorize themselves as Puerto Rican or Cuban or Mexican, and that didn’t work well, barely anyone answered, but the, “Check here if you are Hispanic” question seemed to get the largest response. However, in a 2010 study, when when people were contacted who checked both “white” and “Hispanic” and asked if they considered themselves white, less than half of them identified that way. They just didn’t feel they fit into any other category.

When I was in college, I took a masters summer program at NYU called “The Cultural Imperative” where we went to Puerto Rico and learned about it’s colonization, economy, race relations and infrastructure. One of the most overwhelming issues is that over 70% of the population checked “white” on the census. They attributed this to many issues. One was a lack of culturally appropriate language — Latinos might say Mestizo, Indesito, Mulatto, Negro, Blanquito to differentiate between skin tones and characteristics. When race is diluted to only having the options of Black and white, especially in Latinx communities with ancestry comprised of European, Indigenous and African components, it’s often easier to check the box that says “white” than grapple with your family tree. We’ve also all been told and shown over and over that the lighter you are, the more privilege, power and security you have in America.

What Is Considered Mulitracial?

Whether biracial (two races) or multiracial (multiple races), the noteworthy element of these terms is first and foremost understanding what constitutes a race. Someone who is Korean and Chinese is most likely not biracial because both of their ethnicities can be categorized under the race “Asian.” But this can get far more complicated. What about someone who is Dominican and Argentinian? Both countries speak Spanish, though Dominicans are considered Hispanic and Argentinians are considered European. The real question is, what does this person look like? Are they dark skinned or fair? Do they have Indigenous features? Where were they born? What does the world see when they look at them without any context of their ancestry? This is why race can be complicated. The answer, based on the social construct of race, would be most closely tied to the color of their skin.

In and of itself, race is based on appearance alone. Bringing it back to my experience with race, my mom is Puerto Rican and my dad is Dominican. They are both from the Caribbean, speak similar dialects of Spanish and have similar ancestry — a mix of Spanish, Taino and African descendants. My dad is a little darker than me and my mom a little lighter. As a kid I grappled with this idea of what water fountain I would be allowed to drink from during segregation in the Jim Crow South as I learned about it in history class—was I light enough to call myself white or dark enough to be considered Black? As I got older my parents told me they always checked off “Black” on forms and I felt confused because we spoke Spanish at home so weren’t we just Hispanic? This is why I mentioned earlier that I am not multiracial, both of my parents are Black, so I am Black. A Black Latina. Labels can be exhausting, but as I said earlier, then can also be nuanced and useful.

I share my personal story around race and identity because race and identity is a personal thing. While we can scrutinize the key terms above and delve into history and genetics, unpacking specific geographical ties, identity is shaped from the outside in and the inside out.

Vox talked to 6 mixed-race people in this article and describes that while America is becoming more multiracial, we haven’t reached a “multiracial utopia free of racial strife”. “Multiracial people have long been targets of fear and confusion, from suspicions of mixed people “passing” as white under the Jim Crow system to accusations of not embracing one’s ‘race’ enough.”

The “What Are You” Question

Being asked “What are you?” does not feel good. Starting now, make a decision to stop asking people that question. I’ll drop some better options below, but before you even ask, check in with yourself:

Why do I want to know this person’s race, ethnicity or nationality?

Is this question useful or am I just being nosy (and rude) because I feel they are an “other”?

Is it an appropriate time and setting to ask this question?

Can I offer something about myself while asking something about them?

Once you’ve checked in with yourself, try:

Being specific: “What is your ethnicity?” or “How do you racially identify?” or “What is your nationality?” — and know the difference between ethnicity, race and nationality!

Offer information about why you’re asking: “I’m celebrating Lunar New Year with my husband. He’s Chinese. What’s your ethnicity?”

As we know better, we do better. Don’t make assumptions or feel entitled to someone else’s personal information. See ya next week!

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

The Black Panther Party

The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense was founded in October 1966 in Oakland, California by Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale and the first point of their Ten Point Platform and Program was “We want freedom.” In 1968, the FBI’s first director, J. Edgar Hoover called the Black Panthers, “One of the greatest threats to the nation’s internal security,” because they were angry, organized and defiant. COINTELPRO wanted the Black Panthers exterminated, disgraced and omitted from the history books — and largely succeeded. Today, we focus on the truth of their legacy.

“Black people need some peace. White people need some peace. And we are going to have to fight. We’re going to have to struggle. We’re going to have to struggle relentlessly to bring about some peace, because the people that we’re asking for peace, they are a bunch of megalomaniac warmongers, and they don’t even understand what peace means.”

Hi Friends!

Welcome to Issue 36 of this newsletter! This week’s topic is The Black Panther Party. Writing this newsletter was a clear reminder of why I began writing in the first place, because knowing our history matters, especially when the truth is constantly denied to us through the American public education system. The brief, yet impactful legacy of the BPP is both inspiring and devastating. The assassination of Chairman Fred Hampton has brought me to tears on more than one occasion. The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense was founded in October 1966 in Oakland, California by Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale and the first point of their Ten Point Platform and Program was “We want freedom.” In 1968, the FBI’s first director, J. Edgar Hoover called the Black Panthers, “One of the greatest threats to the nation’s internal security,” because they were angry, organized and defiant. COINTELPRO wanted the Black Panthers exterminated, disgraced and omitted from the history books — and largely succeeded. Today, we focus on the truth of their legacy. Let’s get into it.

Let’s Get Into It

Who Were The Black Panthers?

Founded in 1966 in Oakland, California, the Black Panther Party for Self Defense (BPP) was the era’s most influential militant Black power organization.

Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton founded the Black Panther Party for Self Defense with a slogan of “Power to the People.”

They were inspired by Malcom X and drew on Marxist ideology. The Civil Rights Movement seemed aimed at the Jim Crow South to Seale and Newton, and they wanted to create a movement in the North and the West.

While the Black Panthers were often portrayed as a gang, their leadership saw the organization as a political party whose goal was getting more African Americans elected to political office.

They wore leather jackets, black berets and walked in lock step formations.

They were a sophisticated political organization comprised of predominantly uneducated, young, poor, disenfranchised Black people who realized that through organization and discipline, they could use their talents and resources to make a real impact in their community.

They had a radical political agenda compared to non-violence advocates like Martin Luther King Jr (least we forget King was hated, a target of the FBI, assassinated and murdered).

While the Civil Rights Movement sought equality, the Black Power Movement assumed equality of person, and sought the opportunity to express that equality through pride.

Women made up about half of the Panther membership and often held leadership roles.

At its peak in 1968, the Black Panther Party had roughly 2,000 members.

The party enrolled the most members and had the most influence in the Oakland-San Francisco Bay Area, New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Seattle, and Philadelphia.

They worked with many non-Black folks and organizations, with Bobby Seale stating: “The biggest misconception is the FBI said that the Black Panthers hated all white folks. How could we hate white folks when we protested along with thousands of our white left radical and white liberal friends? We worked in coalition with each other, in coalition with the Asian community organizations and coalition with Native American community organizations, in coalition with Hispanic, Puerto Ricans and brown [people]. I had coalitions with 39 different organizational groups crossing all racial and organizational lines.”

The Ten Point Platform

We want freedom. We want power to determine the destiny of our Black Community.

We want full employment for our people.

We want an end to the robbery by the Capitalists of our Black Community.

We want decent housing, fit for shelter of human beings.

We want education for our people that exposes the true nature of this decadent American society. We want education that teaches us our true history and our role in the present day society.

We want all Black men to be exempt from military service.

We want an immediate end to POLICE BRUTALITY and MURDER of Black people.

We want freedom for all Black men held in federal, state, county and city prisons and jails.

We want all Black people when brought to trial to be tried in court by a jury of their peer group or people from their Black Communities, as defined by the Constitution of the United States.

We want land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice and peace.

Why Were They Feared By White America?

The New York Times wrote an article claiming responsibility for their portrayal of The Black Panther Party, stating: “The media, like most of white America, was deeply frightened by their aggressive and assertive style of protest,” Professor Rhodes said. “And they were offended by it.”

The media called them “antiwhite” (though the Panthers frequently called on ALL Americans to fight for equality) and constantly focused on their guns and militant style.

When discussing clashes with police, the media focused on the altercation, not the critique of police brutality — something Black America continues to deal with to this day. What went largely unreported was the fact that these conflicts stemmed not just from the Panthers, but also from the federal government.

It was not until years later that the Senate’s Church Committee would show how pervasively the F.B.I. worked against the Panthers and how much it influenced press coverage. It encouraged urban police forces to confront Black Panthers; planted informants and agents provocateurs; and intimidated local community members who were sympathetic to the group. The Panther-police conflict that inevitably followed played directly into the narrative that had been established: that the party was a provocative, dangerous organization.

What Did The Black Panthers Do?

Although created as a response to police brutality, the Black Panther Party quickly expanded to advocate for other social reforms:

Local chapters of the Panthers, often led by women, focused attention on community “survival programs.”

A free breakfast program for 20,000 children each day as well as a free food program for families and the elderly.

They sponsored schools, legal aid offices, clothing distribution, local transportation, and health clinics and sickle-cell testing centers.

They created Freedom Schools in nine cities including the noteworthy Oakland Community School.

They practiced copwatching, observing and documenting police activity in Black communities. They often did this with loaded firearms because they advocated for armed self defense. The BPP rejected nonviolence as both a tactic and a philosophy, emphasizing instead the importance of physical survival to the continuing struggle for civil and human rights.

Prominent Members

How Were They Destroyed?

The Mulford Act of 1967 in California was a state-level initiative that prohibited the open carry of loaded firearms in public spaces as a direct response to the BPP. The Black Panther Party sparked fear among policymakers, who translated these anxieties into legislation designed to undermine this social activism. Because the BPP relied on strategies (like having firearms) that were not widely used by mainstream civil rights activists, the group faced new forms of legal repression. Policymakers successfully employed gun control legislation to undercut the BPP. By criminalizing the BPP’s use of weapons on California streets, the Mulford Act weakened the BPP and provided opportunities to show them breaking the law.

In 1969, COINTELPRO (a branch of the FBI aimed at surveilling, infiltrating, discrediting, and disrupting domestic American political organizations) targeted the Panthers for elimination — shown in various documents.

FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, who deemed the Black Panther Party a threat to American security, launched a counterintelligence attack against the group, which included infiltrators and deadly raids. By the time the group was dismantled in the mid-1970s, 28 members were dead. 750 Panthers were imprisoned. Systematically, the local and federal authorities dismantled the organization.

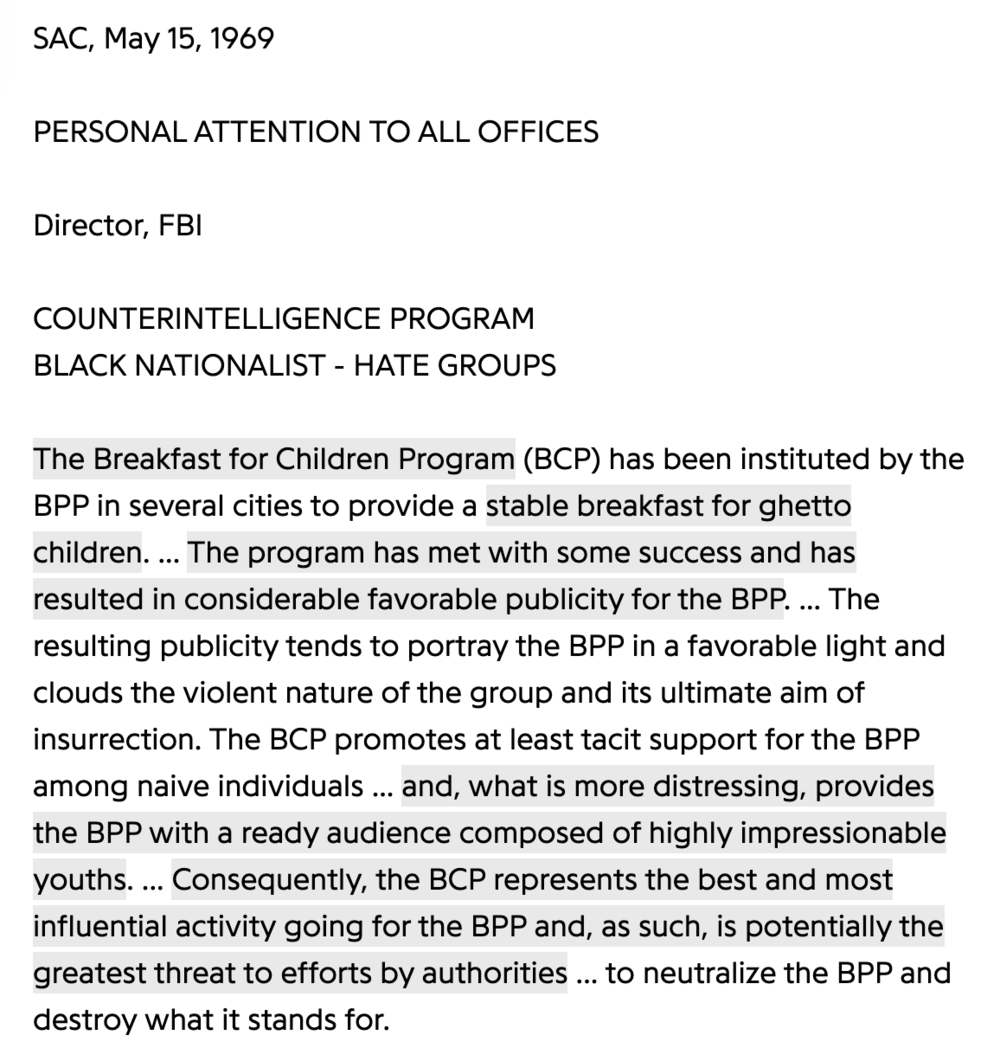

Read FBI director J. Edgar Hoover’s statement from May 15, 1969 calling “to neutralize the BPP and destroy what it stands for.’

Today, American children learn a false and warped history of The Black Panther Party. Teachers’ Curriculum Institute’s textbook History Alive! The United States Through Modern Times states: “Black Power groups formed that embraced militant strategies and the use of violence. Organizations such as the Black Panthers rejected all things white and talked of building a separate black nation.” Holt McDougal’s textbook The Americans reads: “Huey Newton and Bobby Seale founded a political party known as the Black Panthers to fight police brutality in the ghetto.” This same textbook then says, “Public support for the Civil Rights Movement declined because some whites were frightened by the urban riots and the Black Panthers.”

While there is so much more to unpack about The Black Panther Party and the legacies of some of its most prominent members, I hope this newsletter clarified a lot of omitted history. In a time when critical race theory is under attack, it becomes crystal clear how much has been warped by the media — from news channels to text books — and how much more we need the truth.

See ya next week!

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

Stereotypes: 6

The Jewish Community: Today, about 61% of American adults agree with at least one or more classic anti-Semitic canards, while 1 in 5 believe Jewish-Americans “still talk too much about what happened to them in the Holocaust.” Today, we will continue to unpack these stereotypes while understanding the history and background that’s created these caricatures of the Jewish community in America.

Hi Friends!

Welcome to Issue 36 of this newsletter! It’s the sixth week of our Stereotypes series, and this week we focus on the Jewish community. I grew up in a predominantly white, catholic community, and while I had one or two classmates over the years who were Jewish, I never knew anything about Judaism until I went to college, where two of my roommates were Jewish along with many of my classmates. While I had not encountered many Jewish people in my childhood, I still had a lot of ideas about what they might be like—stereotypes—that I learned from television or pop culture or the things I would overhear classmates or teachers say. This is how stereotypes manifest in our subconscious, most often not based in our lived experiences, but on the caricatures we see in the media. Today, about 61% of American adults agree with at least one or more classic anti-Semitic canards, while 1 in 5 believe Jewish-Americans “still talk too much about what happened to them in the Holocaust.” Today, we will continue to unpack these stereotypes while understanding the history and background that’s created these caricatures of the Jewish community in America.

Key Terms

Jewish: Any person whose religion is Judaism. In the broader sense of the term, a Jew is any person belonging to the worldwide group that constitutes, through descent or conversion, a continuation of the ancient Jewish people, who were themselves descendants of the Hebrews of the Bible (Old Testament).

Anti-Semitism: Anti-Semitism is hostility toward or discrimination against Jews as a religious or racial group. The term anti-Semitism was coined in 1879 by the German agitator Wilhelm Marr to designate the anti-Jewish campaigns under way in central Europe at that time. Although the term now has wide currency, it is a misnomer, since it implies a discrimination against all Semites. Arabs and other peoples are also Semites, and yet they are not the targets of anti-Semitism as it is usually understood. Nazi anti-Semitism culminated in the Holocaust.

Zionism: Zionism is a religious and political effort that brought thousands of Jews from around the world back to their ancient homeland in the Middle East and reestablished Israel as the central location for Jewish identity. While some critics call Zionism an aggressive and discriminatory ideology, the Zionist movement has successfully established a Jewish homeland in the nation of Israel.

“Jewface”: “Jewface” is a term that contemporary audiences are unlikely to recognize, aside from its obvious connection to the term “blackface.” It refers to the vaudeville mainstay of the stage Jew, a Yiddish-speaking, large-nosed, bearded caricature, often played by a non-Jewish actor, that sprang into popular circulation after large numbers of Eastern European Jews began immigrating to the United States in the 1880s. Although such a portrayal would provoke outrage from Jews and non-Jews alike in America today, reactions in the turn-of-the-century Jewish community were mixed. Read more about it and Eddy Portnoy, curator of the new exhibit “Jewface: Yiddish Dialect Songs of Tin Pan Alley” at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research.

Let’s Get Into It

As with every group we have discussed so far, no one group is a monolith. All people have complex backgrounds, beliefs and feelings. But what we are dissecting today are un-truths that you may subconsciously be believing. These archetypes in all communities are offensive because they reduce real people to characters. Let’s dive in and describe some of the most believed stereotypes of the Jewish community in America.

The Greedy, Wealthy Moneylender: One of the most prominent and persistent stereotypes about Jews is that they are greedy and avaricious. They are seen both as relentless in the pursuit of wealth while also as stingy misers. They are imagined to exert control over the world’s financial systems, but are also accused of regularly cheating friends and neighbors. The stereotype of Jewish greed dates back to the Middle Ages. Jews typically had restrictions placed on their economic activity. Sometimes the only option available to earn a living in such circumstances was through high-interest crediting and while Christians were prohibited from moneylending, they often recruited Jews to do this work. This made it easy for leaders to position Jews as a scapegoat and the cause of the common people’s financial woes. Characters like Shylock in The Merchant of Venice reflect this attitude towards Jews being greedy and immoral. Eventually this stereotype worked its way into modern vernacular: “To Jew someone down” became a common expression meaning to bargain for a lower price.

The Jewish Mother: The Jewish Mother is depicted as a “middle-aged woman with a nasal New York accent, who either sweats over a steaming pot of matzah balls while screaming at her kids from across the house. Or, in an updated version, she sits poolside in Florida, jangling her diamonds and guilt-tripping her grown children into calling her more often. She is sacrificing yet demanding, manipulative and tyrannical, devoted and ever-present. She loves her children fiercely, but man, does she nag.” Her predecessor, the Yiddishe Mama, carried little of the negative cultural weight of the Jewish Mother and was celebrated at the turn of the 20th century. The Yiddishe Mama was a sentimentalized figure, a good mother and homemaker, known for her strength and creativity, entrepreneurialism and hard work, domestic miracles and moral force. The Yiddishe Mama reminded Jews of the Old World and was synonymous with nostalgia and longing. But while the Yiddishe Mama and her selfless child-rearing contributed to the success and upward mobility of the American Jewish family, the Jewish mother stereotype became warped as many American Jews rose economically and socially — she was now represented as entitled and overbearing, showy and loud, she became the scapegoat for anxieties around Jewish assimilation and by mid-century, the Jewish mother was primarily identified by negative characteristics, tinged with self-hatred and misogyny.

The JAP (Jewish American Princess): The archetype was forged in the mid-1950s, in concert with the Jewish-American middle-class ascent. The JAP is neither Jewish nor American alone. She makes herself known where these identities collide. As a philosophy, JAP style prioritizes grooming, trepidatious trendiness, and comfort. In any given season, the look is drawn from mainstream fashion trends. “She buys in multiples (almost hysterically in multiples),” wrote Julie Baumgold in a 1971 New York magazine op-ed. “She has safe tastes, choosing an item like shorts when it is peaking.” JAP style is less concerned with capital-F fashion than it is with simply fitting in. JAP is rarely used outside the Jewish world, it is far too acute to be relevant in places where people don’t know many actual Jews. While the Jewish Mother stereotype was designed to absorb the stigmas of the old world, the JAP was designed to absorb the stigmas of the new world. “The JAP was a woman who had overshot the mark, piling on the trappings of the stable middle class like so many diamond tennis bracelets.”

The Jewish Community in Today’s Media

The Anti-Defamation League (ADL), which tracks incidents of anti-Jewish violence and bias, says they saw a 75% increase in anti-Semitism reports to the agency's 25 regional offices after the most recent Israeli-Palestinian conflict. You can read my previous newsletter on the conflict here.

While depictions of Jewish people in the media have improved — with shows like “Unorthodox,” “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel,” “Curb Your Enthusiasm” and “Shtisel” all focusing their attention on Jewish characters making their way through the world, often through a positive lens — there are still displays of these stereotypes shown.

I’ve heard my Jewish friends say they often feel excluded from conversations about discrimination and prejudice in America. That antisemitism is often seen as something separate from the discrimination other marginalized folks encounter. The history of Jews being stigmatized, stripped of their rights, forced into ghettos as early as 1516 Venice, banished from cities and towns, murdered and ostracized is overwhelming. While Jewish Americans make the highest income of all religious groups in America, these stereotypes of greed and avarice are simply not true, and make it easy to ignore the historical discrimination of Jewish people around the world. As with all of these newsletters, take some time to reflect on any implicit biases you may be harboring and continue to learn more.

Next week, I’m talking about the real history of the Black Panther Party and I am EXCITED about this one. See ya there!

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

The 4th of July

We’ve learned from elementary school through adulthood that this is a holiday meant to celebrate liberty and freedom, but who did the Founding Fathers seek to celebrate when they signed the Declaration of Independence? Whose freedom was secured when 41 out of the 56 men who signed that document owned slaves?

“What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer: a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. ”

Hi Friends!

Welcome to Issue 35 of this newsletter! Today we are talking about The 4th of July. We’ve learned from elementary school through adulthood that this is a holiday meant to celebrate liberty and freedom, but who did the Founding Fathers seek to celebrate when they signed the Declaration of Independence? Whose freedom was secured when 41 out of the 56 men who signed that document owned slaves? Let’s get into it.

Let’s Get Into It

The 4th of July commemorates the passage of the Declaration of Independence by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776.

From 1776 to the present day, July 4th has been celebrated as the “birth of American independence”.

Important Dates to Remember:

The end of slavery: January 31, 1865 (The 13th Amendment)

The right to vote for women: August 26, 1920 (The 19th Amendment)

The right to vote for non-white Americans: May 26, 1965 (Voting Rights Act of 1965)

The end of Jim Crow South: 1960s

The legalization of same-sex marriage: June 26, 2015 (Obergefell v. Hodges)

In 1776, who’s independence was being celebrated?

Not enslaved Americans (86 years until the end of slavery).

Not women (144 years until women will have the right to vote).

Not people of color (189 years until the Voting Rights Act).

Not Black Americans (about 189 years until the end of Jim Crow Laws).

Not gay or queer Americans (239 years until same sex marriage).

And still today we wait for so much more equality for the majority of Americans — POC, Indigenous, Black, Queer, Trans* Americans and so many others.

In 1852 (13 years before the end of slavery), Fredrick Douglas delivered one of his most famous speeches, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” Watch his descendants recite some of his most poignant lines.

As you barbecue and ignite fireworks this 4th of July, remember that many still wait for the promise of liberty and justice. That freedom has yet to be granted to all.

Pride Month

We are focusing on LGBTQ+ Pride Month, which is celebrated in June throughout the United States. Black queer and trans* women have always been at the forefront of LGBTQ+ activism, and we remember the large role they played during The Stonewall Riots of 1969, commemorated every Pride.

Hi Friends!

Welcome to Issue 34 of this newsletter! Today we are focusing on LGBTQ+ Pride Month, which is celebrated in June throughout the United States. Black queer and trans* women have always been at the forefront of LGBTQ+ activism, and we remember the large role they played during The Stonewall Riots of 1969, commemorated every Pride. Let’s review some key terminology, check out a brief history of gay rights in America, and then close with some additional resources and activists to continue to learn from. Let’s get into it.

Key Terms

Gender: Gender refers to the socially constructed characteristics of women and men, such as norms, roles, and relationships of and between groups of women and men. It varies from society to society and can be changed.

Sex: “Sex” tends to relate to biological differences. For instance, male and female genitalia, both internal and external and the levels and types of hormones present in male and female bodies.

Sexual Orientation: An inherent or immutable enduring emotional, romantic or sexual attraction to other people.

Gender Identity: One’s innermost concept of self as male, female, a blend of both or neither – how individuals perceive themselves and what they call themselves. One's gender identity can be the same or different from their sex assigned at birth.

Pronouns: Pronouns are words that refer to either the people talking (like you or I) or someone or something that is being talked about (like she, they, and this). Gender pronouns (like he or them) specifically refer to people that you are talking about. Examples: she/her, he/him, they/them, ze/hir.

Queer: An umbrella term to describe individuals who don’t identify as straight and/or cisgender.

Trans*: An umbrella term covering a range of identities that transgress socially-defined gender norms. Trans with an asterisk is often used in written forms (not spoken) to indicate that you are referring to the larger group nature of the term, and specifically including non-binary identities, as well as transgender men (transmen) and transgender women (transwomen).

Gender Non Conforming: A gender descriptor that indicates a non-traditional gender expression or identity. A gender identity label that indicates a person who identifies outside of the gender binary.

Cisgender: A gender description for when someone’s sex assigned at birth and gender identity correspond to their gender identity.

Non Binary: Noting or relating to a person with a gender identity or sexual orientation that does not fit into the male/female or heterosexual/gay divisions.

Let’s Get Into It

A Brief History

In 1779, Thomas Jefferson proposes Virginia law to make sodomy punishable by mutilation rather than death. Bill 64 stated: “if a man, by castration, if a woman, by cutting thro' the cartilage of her nose a hole of one half inch diameter at the least.”

The Harlem Renaissance was from 1917 to 1935. Historians have stated that the renaissance was “as gay as it was black.” Some of the lesbian, gay or bisexual people of this movement included writers and poets such as Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen and Zora Neale Hurston; Professor Alain Locke; music critic and photographer Carl Van Vechten, and entertainers Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, Ethel Waters and Gladys Bentley.

In 1924, Henry Gerber, a German immigrant, founded in Chicago the Society for Human Rights, the first documented gay rights organization in the United States. Soon after its founding, the society disbands due to political pressure and frequent police raids.

In 1950, a Senate report titled "Employment of Homosexuals and Other Sex Perverts in Government" is distributed to members of Congress. The report states since “homosexuality is a mental illness, homosexuals constitute security risks" to the nation because "those who engage in overt acts of perversion lack the emotional stability of normal persons." More than 4,380 gay men and women had been discharged from the military and around 500 fired from their jobs with the government.

In April of 1952 the American Psychiatric Association lists “homosexuality” as a sociopathic personality disturbance. That same year Christine Jorgensen became one of the most famous transgender people when she underwent gender affirming surgery and went on to a successful career in show business.

On April 27, 1953 President Dwight Eisenhower signs Executive Order 10450, banning gay people from working for the federal government or any of its private contractors.

On January 1, 1962 Illinois repeals its sodomy laws, becoming the first U.S. state to decriminalize homosexuality.

On April 21, 1966 Members of the Mattachine Society stage a "sip-in" at the Julius Bar in Greenwich Village, where the New York Liquor Authority prohibits serving gay patrons in bars on the basis that homosexuals are "disorderly." The New York City Commission on Human Rights declares that homosexuals have the right to be served.

A few years later, in 1969 were The Stonewall Riots. The Stonewall Inn was a gay bar in Greenwich Village in New York City. In response to an unprovoked police raid on an early Saturday morning, over 400 people, including gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender and straight people protested their treatment and pushed the police away from the area. Some level of rioting continued over the next six nights, which closed the Stonewall Inn. The Stonewall Riots became a pivotal, defining moment for gay rights. Key people at the riots who went on to tell their stories were: Sylvia Rivera, Martha P. Johnson, Dick Leitsch, Seymore Pine and Craig Rodwell.

In 1970, at the one-year anniversary of the Stonewall Riots, New York City community members marched through local streets in commemoration of the event. Named the Christopher Street Liberation Day, the march is now considered the country’s first gay pride parade.

In 1977, the New York Supreme Court ruled that transgender woman Renée Richards could play at the United States Open tennis tournament as a woman.

On November 8, 1977 Harvey Milk wins a seat on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors and is responsible for introducing a gay rights ordinance protecting gays and lesbians from being fired from their jobs. Milk asked Gilbert Baker, an artist and gay rights activist, to create an emblem that represents the movement and would be seen as a symbol of pride. Baker designed and stitched together the first rainbow flag, which he unveiled at a pride parade in 1978.

In 1981, The New York Times prints the first story of a rare pneumonia and skin cancer found in 41 gay men in New York and California. The CDC initially refers to the disease as GRID, Gay Related Immune Deficiency Disorder. When the symptoms are found outside the gay community, Bruce Voeller, biologist and founder of the National Gay Task Force, successfully lobbies to change the name of the disease to AIDS.

In 1992, Bill Clinton, during his campaign to become president, promised he would lift the ban against gays in the military. But after failing to garner enough support for such an open policy, President Clinton in 1993 passed the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” (DADT) policy, which allowed gay men and women to serve in the military as long as they kept their sexuality a secret. Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell was officially repealed on September 20, 2011.

September 21, 1996, President Clinton signs the Defense of Marriage Act into law. The law defines marriage as a legal union between one man and one woman and that no state is required to recognize a same-sex marriage from out of state.

In 2004, Massachusetts becomes the first state to legalize gay marriage. The court finds the prohibition of gay marriage unconstitutional because it denies dignity and equality of all individuals.

On November 4, 2008, California voters approved Proposition 8, making same-sex marriage in California illegal.

In 2009, The Matthew Shepard Act is passed by Congress and signed into law by President Obama on October 28th. The measure expands the 1969 U.S. Federal Hate Crime Law to include crimes motivated by a victim's actual or perceived gender, sexual orientation, gender identity or disability.

On June 26, 2015, with a 5-4 decision in Obergefell v. Hodges, the U.S. Supreme Court declares same-sex marriage legal in all 50 states.

In 2016, the U.S. military lifted its ban on transgender people serving openly, a month after Eric Fanning became secretary of the Army and the first openly gay secretary of a U.S. military branch. In March 2018, Donald Trump announced a new transgender policy for the military that again banned most transgender people from military service. On January 25, 2021—his sixth day in office—President Biden signed an executive order overturning this ban.

In 2021, Florida, South Dakota, Mississippi, Arkansas, Tennessee, West Virginia, Montana and Alabama have enacted anti-trans sports bans. Under the law, public secondary school and college sports teams are required to be designated based on "biological sex," thus prohibiting trans women and girls from participating on women's athletic teams.

Today, universal workplace anti-discrimination laws for LGBTQ+ Americans is still lacking. Gay rights proponents must also content with an increasing number of “religious liberty” state laws, which allow business to deny service to LGBTQ+ individuals due to religious beliefs, as well as “bathroom laws” that prevent trans* individuals from using public bathrooms that don’t correspond to their assigned sex at birth.

Pride Month

Pride month commemorates The Stonewall Riots in June of 1969. It is an entire month dedicated to the uplifting of LGBTQ+ voices, celebration of LGBTQ+ culture and the support of LGBTQ+ rights.

In the rainbow pride flag, each color has a meaning. Red is symbolic of life, orange is symbolic of spirit, yellow is sunshine, green is nature, blue represents harmony and purple is spirit. In 2021, the flag has was altered in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter protests, including black to represent diversity, brown to represent inclusivity and light blue and pink, the colors of the trans pride flag, along with t purple circle to represent the intersex community.

Pride was made possible through the sacrifices of Black queer and trans women like Marsha P. Johnson who paved the way and continue to be the most vulnerable, most targeted, and most at risk in the community.

Resources

The best Pride Month is an intersectional Pride Month. That means whether someone is “out” or not, queer, gay, non-binary, intersex, gender non-conforming, or any other identity, Pride is still for them. Happy Pride to all of my queer siblings, see ya next time!

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

Juneteenth

Juneteenth became national holiday this week. Juneteenth is an incredibly meaningful moment because enslaved people longed for freedom for generations, and Juneteenth represents that liberation. Why was it so easy to get this date made into a national holiday, yet it is still so hard for Black Americans to have their basic freedoms ensured?

Hi Friends!

Welcome to Issue 33 of this newsletter! Today we are focusing on Juneteenth, which just became national holiday this week. Juneteenth is an incredibly meaningful moment because enslaved people longed for freedom for generations, and Juneteenth represents that liberation. While many Black Americans have celebrated Juneteenth for their entire lifetime, there are definitely those that learned about this holiday later in life because it isn’t discussed in most curriculums and was not a national holiday. For most white Americans, Juneteenth is brand new. In this newsletter, I’ll discuss the history of Juneteenth, and encourage you to watch the clip below. I also want to encourage you to celebrate this holiday appropriately. This holiday may not be for you, and that’s okay. While it was so easy to pass it through senate and get Juneteenth approved on a national scale, it continues to be difficult for Black people to get their basic freedoms guaranteed. This Juneteenth is a great time to consider how you, as an ally, can help to achieve that. Let’s get into it!

Let’s Get Into It

A Brief History

Juneteenth marks the day when federal troops arrived in Galveston, Texas in 1865 to take control and ensure that all enslaved people be freed.

The Emancipation Proclamation was signed, after a very bloody civil war, in 1862 (over two years prior), making chattel slavery illegal, but the United States was still in a vulnerable position, with the south having succeeded, and President Lincoln’s policies had to be enforced through federal soldiers.

General Order No.3 lead to 4 million newly freed Black Americans and they found themselves a very hostile, racist society.

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor.” - General Order No.3

The military stepped in to ensure Black Americans received food, medical care and were protected from violence. When they left the south, it was a signal to southerners that the Federal Government would not protect the rights of Black people. Black folks were lynched and brutalized with impunity. There is still no anti-lynching law in America today.

There has always been constant, random, racist violence inflicted on Black people in this country and it continues today.

Juneteenth honors the end of slavery while also acknowledging that Black Americans continue to be marginalized and disenfranchised

This year, the senate unanimously passed a bill making Juneteenth a national holiday.

Juneteenth

As an ally to the Black community, Juneteenth should be a moment of reflection, contemplation, un-learning and reevaluating. Only 156 years ago troops marched into Texas. Still today, Black Americans are policed, villainized, disenfranchised and subjected to violence. Still today, schools around our nation are banned from teaching critical race theory. Still today, police benefit from qualified immunity, the same police who began as slave catchers. And today, jails will be closed on Juneteenth to celebrate its first year as a national holiday, as an overwhelming number of Black bodies sit in cages. So if this Juneteenth you have the day off of work, use it to amplify this message, to learn this history, to reflect on how a system that exploits Black humans has built your America.

As for my Black siblings this Juneteenth, you know what to do. Whatever you want. Whether that means kicking back at a family BBQ or taking a nap. It might mean showing up for a full day of work like you always do—since we know Black workers make up the largest percentage of front-line workers in America and will most likely not receive a day off on this national holiday. Feel however you want to feel, and do whatever you need to do this Juneteenth.

Next week, we wrap up June chatting about Pride Month and then circle back to our series on Stereotypes. I’ll see you there!

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

Stereotypes: 5

The Indigenous Community: Constantly, we see the oversimplification of Indigenous cultures into one homogenous group. The stereotyping of American Indians must be understood in the context of history which includes conquest, forced displacement, and organized efforts to eradicate native cultures. Though there are indigenous cultures across the globe from Inuit people to First Nations people to Aboriginals, today we’re going to keep the focus on the USA.

Hi Friends!

Welcome to Issue 32 of this newsletter! It’s the fifth week of our Stereotypes series, and this week we focus on the Indigenous or Native community. Constantly, we see the oversimplification of Indigenous cultures into one homogenous group. The stereotyping of American Indians must be understood in the context of history which includes conquest, forced displacement, and organized efforts to eradicate native cultures. Though there are indigenous cultures across the globe from Inuit people to First Nations people to Aboriginals, today we’re going to keep the focus on the USA. Let’s get into it!

Key Terms

American Indian, Native, Native American, Indigenous American: All of these terms are considered acceptable. In the United States, Native American has been widely used but is falling out of favor with some groups, and the terms American Indian or Indigenous American are preferred by many Native people. The consensus, however, is that whenever possible, Native people prefer to be called by their specific tribal name. All global terminology must be used with an awareness of the stereotype that "Indians" are a single people, when in fact there are hundreds of individual ethnic groups, who are all native to the Americas. This type of awareness is obvious when European Americans refer to Europeans with an understanding that there are some similarities, but many differences between the peoples of an entire continent.

Let’s Get Into It

Check out my past newsletter on Mental Health in the Indigenous Community for more history and background.

First and foremost, there are many historical misconceptions when it comes to Natives. From the earliest period of European colonization, images of Natives found expression in drawings, engravings, portraiture, political prints, maps and cartouches, tobacconist figures, weather vanes, coins and medals, and books and prints, and these depictions have shaped a lot of the public’s perception of them. There is the myth that they are nearly extinct, when there are 6.79 million in the United States as of 2021, making up over 2% of the population. From the story of Pocahontas to, the tale of the first Thanksgiving, to the purchase of Manhattan by European settlers—many of the most common tales that we are taught in school and showed in pop culture are lies. We also almost always see Natives in historical settings, as if they don’t continue to live and change today, but are just fixtures of the past. Let’s dive into some of the most common stereotypes.

The Drunk: Few images of Native peoples have been as damaging as the trope of the “drunken Indian”. It has been used to support the claims of Indian inferiority that have resulted in loss of culture, land, and sovereignty. The drunken Indian male is often seen as morally deficient because of his inability to control himself, making him a menace to society. Or he has become alcoholic because of his tragic inability to adjust to the modern world and he is pitied. In contrast to enduring stories about extraordinarily high rates of alcohol misuse among Native Americans, University of Arizona researchers have found that Native Americans’ binge and heavy drinking rates actually match those of whites. The groups differed regarding abstinence: Native Americans were more likely to abstain from alcohol use.

The Warrior: American Indians are represented as barbarous, with tomahawk and scalping knife in hand while European Americans are depicted as innocent victims of savagery. Meanwhile, it was the Europeans who decimated their lands, infected them with diseases, commited genocide, captured their children and tried to eradicate Native culture completely. William “Buffalo Bill” Cody and other showmen, including Plains Indians, drew huge audiences. These shows, and related influences, inspired filmmakers to produce Westerns depicting hordes of Natives attacking European settlers.

Braves/ Chiefs: We most commonly hear these names and see these symbols as mascots. Much like blackface, such inventions and imaginings, meant to represent a racial other, tell us much more about European Americans than they do about Natives. Teams with “Indian” names come with a variety of practices, among them the adoption of “red-face” mascots costumed as Plains Indians, ersatz Indian dances and rituals at halftime, face paint and feathered headdresses, and the antics of war whooping, tomahawk chopping fans. See an updated list on current teams with Native mascots here. There are still hundreds.

The Indian Princess: The term "princess" was often mistakenly applied to the daughters of tribal chiefs or other community leaders by early American colonists who mistakenly believed that Indigenous people shared the European system of royalty. Frequently, the "Indian Princess" stereotype is paired with the "Pocahontas theme" in which the princess offers herself to a captive Christian knight, a prisoner of her father, and after rescuing him, she is converted to Christianity and live with him in his native land. In this way, Native women are objectified and sexualized.This objectification of Indigenous women has lead to a human rights crisis known as Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW). Statistics show that Indigenous women and girls are ten times more likely to be murdered than any other ethnicity.

The Costume: “While minstrel shows have long been criticized as racist, American children are still socialized into playing Indian. Columbus Day celebrations, Halloween costumes and Thanksgiving reenactments stereotype Indigenous Peoples as one big distorted culture. We are relegated to racist stereotypes and cultural caricatures.”

In a study by Children NOW, a child advocacy organization examining children’s perceptions of race and class in the media, Native youngsters said they see themselves as “poor,” “drunk,” “living on reservations,” and “an invisible race.” These stereotypes are seen in everything from cartoons to sporting events, and it’s no wonder why Indigenous people feel invisible, especially when it is America’s best interest to do so.

Next week, I’m celebrating one year of having this newsletter! The following I’ll be talking about Juneteenth, and the last week of June I’ll write about LGBTQ+ Pride Month and “rainbow washing”. We’ll resume the stereotype series with a focus on the stereotyping of the Jewish community in July. I’ll see you there!

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

Stereotypes: 4

The Asian Community: From fetishization to emasculation to feeling like a perpetual outsider, Asian-Americans experience constant “othering”. If you’re looking for more history and background on the AAPI community, definitely read this past newsletter. Today we’ll be breaking down some specific stereotypes and connecting it to the past.

Hi Friends!

Welcome to Issue 31 of this newsletter! It’s the fourth week of our Stereotypes series, and this week we focus on the Asian-American community. My partner Richard—who is Chinese, Korean and Puerto Rican—and I are a part of the 3% of the US population that are in an interracial couple comprised of a predominantly Asian male and Hispanic female, according to Pew Research. In creating this newsletter, as I did when creating my newsletter about Anti Asian Violence During COVID, I asked him about his experiences in America as someone who identifies and exists in this society as an Asian man. From fetishization to emasculation to feeling like a perpetual outsider, his experiences are similar to those of many Asian-Americans. If you’re looking for more history and background, definitely read this past newsletter, today we’ll be breaking down some specific stereotypes and connecting it to the past. Let’s get into it!

Key Terms

Xenophobia: The fear or hatred of that which is perceived to be foreign or strange. It is an expression of perceived conflict between an ingroup and an outgroup and may manifest in suspicion by the one of the other's activities, a desire to eliminate their presence, and fear of losing national, ethnic or racial identity.

Chinese Exclusion Act: In the spring of 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed by Congress and signed by President Chester A. Arthur. This act provided an absolute 10-year moratorium on Chinese labor immigration. For the first time, Federal law proscribed entry of an ethnic working group on the premise that it endangered the good order of certain localities.

Japanese Internment Camps: These were established during World War II by President Franklin Roosevelt through his Executive Order 9066. From 1942 to 1945, it was the policy of the U.S. government that people of Japanese descent would be interred in isolated camps. Enacted in reaction to Pearl Harbor and the ensuing war, the Japanese internment camps are now considered one of the most atrocious violations of American civil rights in the 20th century.

Let’s Get Into It

For more on Yellow Peril, the Chinese Exclusion Act, Japanese Internment Camps and other background, read this newsletter first.

Asian Americans, who represent 6% of the US population, report less discrimination in employment, housing and criminal justice compared with other racial minorities in the United States (Discrimination in America, Harvard Opinion Research Program, 2018). But they often fall victim to a unique set of stereotypes—including the false belief that all Asian Americans are successful and well adapted. Let’s dive into the most common.

Model Minority: East Asians in the United States have been stereotyped as possessing positive traits such as being seen as being hardworking, industrious, studious, and intelligent people who have elevated their socioeconomic standing through merit, persistence, self-discipline and diligence. Between 1940 and 1970, Asian Americans not only surpassed African Americans in average household earnings, but they also closed the wage gap with whites. Hilger’s research suggests that Asian Americans started to earn more because their fellow Americans became less racist toward them. Embracing Asian Americans “provided a powerful means for the United States to proclaim itself a racial democracy and thereby credentialed to assume the leadership of the free world,” Ellen Wu writes in her book “The Color of Success”. Stories about Asian American success were turned into propaganda. By the 1960s, anxieties about the civil right movement caused white Americans to further invest in positive portrayals of Asian Americans. The image of the hard-working Asian became an extremely convenient way to deny the demands of African Americans. Both liberal and conservative politicians pumped up the image of Asian Americans as a way to shift the blame for Black poverty. This is the birth of the Model Minority stereotype.

Yellow Peril: The term “yellow peril” originated in the 1800s, when Chinese laborers were brought to the United States to replace emancipated Black communities as a cheap source of labor. Chinese laborers made less than their white counterparts, and also became victims of racist backlash from white workers who saw them as a threat to their livelihood. This fear led to the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the first law to restrict immigration based on race. Overall, Yellow Peril is the fear of the Asian man coming to America to take jobs away from the white population.

Forever Foreigner: The Forever Foreigner is constantly asked, “Where are you really from?” Asian characters are often portrayed as being unable to assimilate, speak English and create a sense of home in America. This idea helped lay the groundwork for Japanese internment during World War II, when Japanese American citizens were sent to detention camps solely on the basis of their ethnicity, due to suspicions that they were abetting the Japanese government in some way. In the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, Islamophobia toward Muslim Americans and prejudice toward South Asian Americans was similarly fueled by assumptions that people were not loyal to the United States because of their religion, ethnicity and external appearance.

ABG (Asian Baby Girl): Asian Baby Girls are seen as rebellious, replacing polite, studious cultural norms with being loud and taking up space; however, there are both negative and positive connotations for those that are self proclaimed ABGs. Birthed out of 90s club culture, it’s described here by NY locals as a reaction to Chinatown gangs being largely imprisoned, and the community that was left creating this subculture of Asian Baby Gangsters. Asian Baby Gangsters sprang up as a way to gain social capital, a familiar teenage defence mechanism to fit in and advance themselves within their communities. It’s taken on various characteristics since the 90s but is used frequently on TikTok and Instagram today as both a self proclaimed title, and a jab at an Asian girl, similar to the “Dumb Blonde” stereotype.

Effeminate Asian Man: As a way of minimizing the threat posed by Chinese men -- who were often portrayed as stealing white Americans' jobs and women -- Asians were characterized as passive, effeminate and weak. These stereotypes were further promoted in movies, where white actors like Mickey Rooney (Mr. Yunioshi in "Breakfast at Tiffany's") and Warner Oland (who played both Fu Manchu and the fictional detective Charlie Chan), used thick, stunted accents and exaggerated mannerisms to reinforce existing stereotypes, ridiculing or villainizing Asian men as a form of entertainment.

Dragon Lady: The dragon lady is a stereotype portraying East Asian women as domineering, deceitful, mysterious and sexually alluring creatures. The stereotype finds its history in the Yellow Peril movement and the Pace Act of 1875, which barred Asian women from entering the US. This not only branded the women as unwelcome, but also essentially a threat to white supremacy. Another view is that the dragon woman is someone who needs to be “civilized” for western culture. The U.S. military contributed to this conception of Asian women as hypersexualized. During the wars in the Philippines at the start of the 19th century, and during the mid-20th-century wars in Korea and Vietnam, servicemen took advantage of women who had turned to sex work in response to their lives being wrecked by war.

The Lotus Blossom: The Lotus Blossom Lady, also known as China Doll or Geisha Girl, is the very symbol of feminine Asian “flowers” – the complete opposite of the sexual Dragon Lady. The modest butterfly known as the Lotus Blossom Lady is demure, innocent, gentle, but most of all, obedient.Unlike the Dragon Lady who needs to be conquered, the gentle China Doll needs to be saved by the Western man, someone who can take care of her fragile, almost child-like self. Above all, she is a good girl, making her the perfect wife.

Like every community we have discussed thus far, the Asian-American community is complex, multifaceted and far from a monolith. Next week, let’s talk about stereotypes surrounding the Indigenous community in The United States. See ya there!

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

Israel and Palestine

Today I’m sharing resources in regard to the current conflicts between Israel and Palestine. In this moment, I want to be clear that it would be inappropriate for me to center myself and my opinions. My goal is to share resources and amplify those that know more than me in this area. Above all, my goal is to continue to encourage each and every person to actually take time to learn before you talk about a topic as if you have all of the information. Like all things, it’s going to take time, effort and some discomfort, to grapple with realities that are complex and nuanced.

Hi Friends!

Welcome to Issue 30 of this newsletter! Today I’m sharing resources in regard to the current conflicts between Israel and Palestine. In this moment, I want to be clear that it would be inappropriate for me to center myself and my opinions. My goal is to share resources and amplify those that know more than me in this area. Above all, my goal is to continue to encourage each and every person to actually take time to learn before you talk about a topic as if you have all of the information. An Instagram infographic doesn’t have all of the answers. A soundbite from the news doesn’t have all of the answers. Like all things, it’s going to take time, effort and some discomfort, to grapple with realities that are complex and nuanced. I will never be silent in the face of oppression, but I will also never jump on a bandwagon without doing my best to fully break down the historical, cultural, economic and political backdrop of a conflict. Do I feel like I have the clearest idea about what is transpiring in the Middle East? No. But I have a greater sense of understanding and I have some very clear tips on how you can do your best to be an ally. Let’s get into it!

Key Terms

Israel: The nation of Israel—with a population of more than 9 million people, most of them Jewish—has many important archaeological and religious sites considered sacred by Jews, Muslims and Christians alike, and a complex history with periods of peace and conflict.

Palestine: Palestinians, the Arab population that hails from the land Israel now controls, refer to the above mentioned territory as Palestine, and want to establish a state by that name on all or part of the same land. The history of Palestine has been marked by frequent political conflict and violent land seizures because of its importance to several major world religions, and because Palestine sits at a valuable geographic crossroads between Africa and Asia. The people of Palestine have a strong desire to create a free and independent state in this contested region of the world.

Gaza Strip: A piece of land located between Egypt and modern-day Israel.

Golan Heights: A rocky plateau between Syria and modern-day Israel.

West Bank: A territory that divides part of modern-day Israel and Jordan.

Jerusalem: Both Jews and Muslims consider the city of Jerusalem sacred. It contains the Temple Mount, which includes the holy sites al-Aqsa Mosque, the Western Wall, the Dome of the Rock and more.

Jewish: Any person whose religion is Judaism. In the broader sense of the term, a Jew is any person belonging to the worldwide group that constitutes, through descent or conversion, a continuation of the ancient Jewish people, who were themselves descendants of the Hebrews of the Bible (Old Testament).

Muslim: 98% of Palestinians identify as Sunni Muslims. The definition of Muslim varies depending on which criteria you use. Most textbooks give a definition based on practice of the “five pillars” of Islam, so that Muslims are those who give the profession of faith, pray five times a day, fast during Ramadan, give charity to the needy, and make the pilgrimage to Mecca at least once during their lifetimes.

Arab: Arab is an ethno-linguistic category, identifying people who speak the Arabic language as their mother tongue (or, in the case of immigrants, for example, whose parents or grandparents spoke Arabic as their native language). Arabic is a Semitic language, closely related to Hebrew and Aramaic. While Arabs speak the same language, there is enormous ethnic diversity among the spoken dialects.

Semitic: Relating to or denoting a family of languages that includes Hebrew, Arabic, and Aramaic and certain ancient languages such as Phoenician and Akkadian, constituting the main subgroup of the Afro-Asiatic family.

Anti-Semitism: Anti-Semitism is hostility toward or discrimination against Jews as a religious or racial group. The term anti-Semitism was coined in 1879 by the German agitator Wilhelm Marr to designate the anti-Jewish campaigns under way in central Europe at that time. Although the term now has wide currency, it is a misnomer, since it implies a discrimination against all Semites. Arabs and other peoples are also Semites, and yet they are not the targets of anti-Semitism as it is usually understood. Nazi anti-Semitism culminated in the Holocaust.

Hamas: The Palestinian militant group that rules Gaza.

Zionism: Zionism is a religious and political effort that brought thousands of Jews from around the world back to their ancient homeland in the Middle East and reestablished Israel as the central location for Jewish identity. While some critics call Zionism an aggressive and discriminatory ideology, the Zionist movement has successfully established a Jewish homeland in the nation of Israel.

Let’s Get Into It

This conflict is complex. Every group can explain why they feel that this land belongs to them and every group has historical, religious and emotional ties to that land. It’s not my place to say who is or isn’t deserving, but I think it’s everyone’s job to understand why folks feel the way they do. Nothing ever justifies bloodshed, displacement or violent. Period. But nonetheless, it is enacted every day around the world. A great place to start finding a solution is understanding the cause. Below is an outline of how I researched this topic. First, I went straight for a historical timeline to understand the background. Then, I checked out some lightly opinionated pieces. Then, I spent a lot of time reading some widely conflicting pieces to get a sense of various perspectives and personal opinions. Below are some of those resources.

Resources

I started my research with these basic timelines of Israel and Palestine.

This video from HISTORY is two years old, but breaks down how the Israel-Palestine conflict began in a relatively neutral way.

I moved into some lightly opinionated pieces from NPR and VOX.

Next, I read a wide range of articles from varied perspectives. Without an entire community of folks for me to interview and learn from personally, I felt like this was the best way for me to understand some conflicting, opposing and complex viewpoints. My goal was overall not to read anything that seemed like propaganda, but to read the most opinionated pieces I could find, within reason.

Many articles like this one from The New York Times describe an internal conflict for the young Jewish community in America being torn between their support of Israel or Palestine. “Many young American Jews are confronting the region’s longstanding strife in a very different context, with very different pressures, from their parents’ and grandparents’ generations.”

This article by The Anne Frank House discusses if all criticism of Israel is anti-Semitic. “Criticism of Israel or of the policies of the Israeli government is not automatically antisemitic. For example, anyone is free to reject or criticise the Israeli government's policy regarding the Palestinian territories. This happens in Israel, too…But it is increasingly difficult to have a proper discussion about 'Zionism' or a normal, critical debate about Israel.”

This article from Yahoo News talks about why “young left-leaning Americans are increasingly using social media to urge more support and aid for Palestinians, framing it as a human rights issue that echoes the antiracism movement from this past year.” It also talks about how “young people are also susceptible to peer pressure to post online about issues to prove that they are engaged.” One opinion in this article states: “On social media, nuanced topics like the Israeli-Palestinian conflict are reduced to “shallow, facile” content rather than seriously explaining the issues.” Another states: “When we’re talking about Israeli violence against Palestinians, it’s not complex at all…Ultimately it’s a cause about total freedom, justice and equality for all people." This article attempts to share varying perspectives and is the most opinionated piece in this line up.

These live updates from The New York Times seem to have the most current information, including the most recent cease fire.

What To Do Next

If you say you’re taking this time to learn, actually learn something about the history of Israel and Palestine.

Slow down the reposts and the likes and fact check what you’re posting. It might take more than one Google search, and that’s okay.

This conflict isn’t the same as #BlackLivesMatter. Neither situation is the same as #StopAsianHate. Not every movement has the same social, historical, political and economic implications and there’s no reason to conflate them. Yes, there are similarities in various systems of oppression, but not all systems operate and exists in the same way.

Whatever your opinion, continue to denounce violence, racism, anti-semitism and hatred of every kind, always.

Friends, this is where I am at thus far with my learning. Have something else to share or a better resource? Send me an email. This was a lot to learn and unravel in a weeks time and there are plenty of areas I’m not knowledgeable of just yet, so let me know what I missed! Next week, we bring it back to the series on Stereotypes. See ya there!

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

Stereotypes: 3

The Latinx Community: Do you know the difference between Hispanic and Latino? Today we start out by unpacking these terms, then dive into some common stereotypes, archetypes and media depictions. While American pop culture confuses Puerto Ricans and Mexicans, Colombians and Brazilians, the Latinx community spans over 33 countries and 2 continents with various cultures, dialects, histories, religions and motivations for immigrating to America.

Hi Friends!